Photo: Verdy Verna

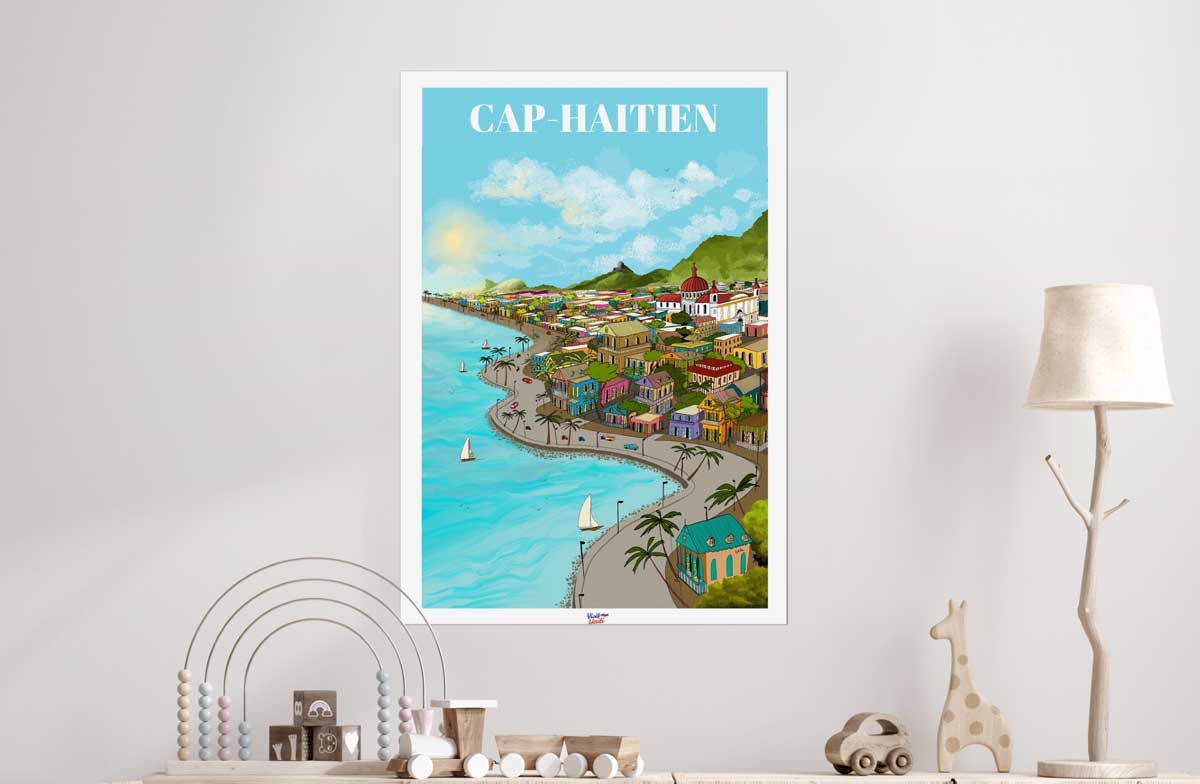

Cap-Haïtien City Guide: 350 Years of Stories, One Unforgettable City

As Haiti’s second-largest city, Cap-Haïtien draws visitors with its rich history, world-class beaches, and UNESCO heritage sites. Join us as we take a swooping dive into the heart of the city and learn how it earned its well-deserved title as The Paris of the Antilles.

Cap-Haïtien is a city that refuses to be rushed. The pastel-colored facades of its colonial-era mansions hint at a storied past, while moto taxis zip through streets where revolution once brewed. Nicknamed The Paris of the Antilles, it was once the wealthiest city in the Caribbean—its grand architecture and rich cultural scene a testament to that golden age.

But Okap isn’t just about history. Mornings here start with strong Haitian coffee on the boulevard, afternoons drift by on palm-fringed beaches, and evenings hum with the rhythm of live konpa music. Whether you’re tracing the footsteps of Haiti’s revolutionaries or diving fork-first into a plate of grilled lambi, this city doesn’t just welcome visitors—it pulls them in.

Photo: Franck Fontain

What to See and Do in Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien is a city best explored at street level. Colonial-era buildings with pastel facades line the streets, moto taxis weave between street vendors, and the scent of sizzling griot drifts from neighborhood eateries. Whether you’re drawn to history, bustling markets, or just soaking in the city’s energy, there’s plenty to take in.

Boulevard du Cap-Haïtien (Boulva Okap)

Start with a leisurely stroll down Boulevard du Cap, or Boulva Okap as locals call it. This waterfront stretch is the city’s beating heart, lined with cafés, restaurants, and bars where Cap-Haïtien comes alive—especially on Sundays, when locals gather to eat, drink, and unwind by the sea.

Want an insider’s perspective? We spoke to Za, a local guide, who shares her go-to spots for food, culture, and nightlife.

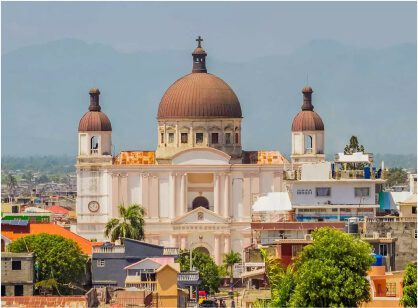

Notre Dame Cathedral

Anchoring Place d’Armes, Cap-Haïtien’s main square, this elegant cathedral is a city icon. First built in the 1600s and later reconstructed in the 20th century, its crisp white facade stands as a backdrop to daily life—street vendors, musicians, and people passing through.

Héros de Vertières

History isn’t just something you read about in Cap-Haïtien—it’s something you stand in. Héros de Vertières is an open-air monument commemorating the 1803 Battle of Vertières, the final fight for Haiti’s independence. A short drive from downtown, this stirring tribute to Jean-Jacques Dessalines and his troops is a must-visit—especially for those tracing their Haitian roots.

Marché Cluny (The Iron Market)

A riot of color, noise, and scent, Marché Cluny—often called Cap-Haïtien’s Iron Market—has been a bustling hub since 1890. Its cast-iron architecture mirrors the iconic Marché en Fer in Port-au-Prince, and inside, you’ll find everything from fresh produce to handcrafted vodou ritual objects. If you’re on the hunt for souvenirs with real character, this is the spot.

Photo: Franck Fontain

Where to Eat & Drink in Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien’s food scene is a celebration of bold flavors and fresh ingredients, with seafood taking center stage. Fried fish, regional cashew-based specialties, and rich, slow-cooked stews fill menus across the city, offering plenty of local flavors to discover.

Here are a few standout spots:

Cap Deli

A go-to for generous portions and creative takes on local flavors, Cap Deli serves up some of the city’s most satisfying comfort food. Try the Meat Overloaded Fries, seafood pizza, or griot pizza, but if you’re looking for something truly special, go for the Bouillon Pêcheur—a rich seafood and vegetable soup packed with flavor.

Boukanye

With its breezy, relaxed vibe, Boukanye is a go-to for hearty Haitian classics. Their poisson gros sel—slow-cooked whole fish in a fragrant broth—is a must-try, especially when paired with diri djon djon, a local specialty made with black mushrooms.

Street food & kleren vendors

Some of the best flavors in Cap-Haïtien are found right on the street. Look out for vendors selling fritay (fried street snacks), crispy pâté (Haitian hand pies), and homemade kleren, Haiti’s artisanal sugarcane spirit. Street vendors often serve cups infused with ingredients like ginger, cinnamon, or medicinal roots that locals swear by. It’s strong—but if you want a real taste of Haiti, this is it.

Want more food recommendations? Check out our full list of Cap-Haïtien’s best restaurants and don’t miss our guide to Haitian street food for a deep dive into the country’s most irresistible bites.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

Best Beaches for Swimming, Snorkeling, and Sunbathing

History may have put Cap-Haïtien on the map, but its beaches keep people coming back. Whether you’re after a quiet stretch of sand, a tropical island escape, or just a good spot to sip an ice-cold Prestige, here’s where to go:

Cormier Plage

Just 20 minutes from downtown, this low-key beach is the kind of place where time slows down. Lounge under the palms, take a dip in the calm waters, and order a fresh seafood lunch without ever leaving your chair.

Île-à-Rat (Amiga Island)

If your idea of paradise is turquoise water, soft white sand, and zero crowds, hop on a boat to Île-à-Rat. This tiny offshore island is a local favorite, perfect for snorkeling, swimming, or just kicking back with a plate of grilled lobster. Make sure you take some bottles of Haitian rum with you for the trip!

Looking for more sun-drenched escapes? Check out our full guide to the best beaches near Cap-Haïtien.

Where to Stay

Cap-Haïtien has stays for every kind of traveler, whether you want ocean views, mountain breezes, or a private island escape. Here are three standout options:

Habitation des Lauriers

Perched above the city, Habitation des Lauriers offers unbeatable panoramic views and a peaceful retreat from the bustle below. The steep road up is no joke, but once you’re there, you’ll be surrounded by cool mountain air and lush greenery. Rooms range from budget-friendly basics to more comfortable options with AC and hot showers. The real highlight? Sunsets from the terrace.

Ekolojik Resort

For a nature-meets-comfort experience, Ekolojik Resort is tucked into the hills outside the city, offering a peaceful escape with views of Cap-Haïtien and the bay. The property is surrounded by fruit trees and lush greenery, and they focus on locally sourced, organic food. If you love waking up to fresh air and birdsong, this is your spot.

Chez Max

Only accessible by boat, Chez Max is a boutique B&B in a private cove, surrounded by tropical forest and turquoise water. The separate bungalows and villa offer a secluded, laid-back atmosphere with kayaks, paddleboards, and a private beach at your doorstep. Add in a delicious, homemade breakfast and it’s the ultimate off-the-grid hideaway.

Want more options? Check out our full guide on where to wake up in Cap-Haïtien.

Photo: Franck Fontain

Nightlife & Live Music in Cap-Haïtien

As the day winds down, Cap-Haïtien doesn’t sleep—it just changes tempo. Locals spill onto terraces, kompa beats hum in the background, and the scent of grilled seafood lingers in the air. From breezy rooftops to beachside bars, here’s where to settle in for a drink and good company.

Lakay

A waterfront favorite for over 25 years, Lakay is as much about good vibes as great drinks. Expect a lively crowd, especially on Sunday nights, and don’t miss Salsa Thursdays, where you can pick up a few moves while sipping on a classic rum sour.

Les 3 Rois

Perched on the coastal road to Labadee, this hotel bar offers a peaceful atmosphere, a sea breeze, and dangerously good cocktails. The cassava accras (manioc fritters) are a mu5st, best paired with a fresh mojito while you watch the waves roll in.

Les Alizés

A stylish rooftop bar with modern architecture and panoramic views over the city. Come at sunset on weekends for an after-work crowd, DJ sets, and an unbeatable view of the Notre Dame Cathedral glowing in the evening light.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

Awesome Day-Trips

Most visitors to Cap-Haïtien make a beeline for Sans-Souci Palace and the Citadelle Henri, the city’s UNESCO-listed crown jewels. And while these historic landmarks are a must, venture a little further, and you’ll find places that feel worlds away—where citrus groves perfume the air, ancient carvings tell forgotten stories, and emerald pools shimmer in the hills. Here are three day trips that take you beyond the usual sights.

Wander Through the Orange Groves of Grand Marnier

Just outside Limonade, rolling fields of bitter orange trees stretch as far as the eye can see. The citrus grown here plays a key role in world-famous liqueurs like Grand Marnier and Cointreau. While official tours aren’t a thing, locals might just invite you to see the groves up close and share a taste of Haiti’s citrus-scented heritage.

Find Ancient Taíno Petroglyphs in Sainte-Suzanne

Hidden in the hills near Foulon, these centuries-old rock carvings whisper the stories of Haiti’s first inhabitants, the Taíno. The petroglyphs are etched into massive boulders, their meaning still a mystery, but their presence a powerful reminder of the island’s deep Indigenous roots. A local guide can help you find them—and share the legends tied to these ancient markings.

Cool Off in the Emerald Waters of Bassin Waka

Near Port-Margot, Bassin Waka is a freshwater oasis surrounded by lush greenery, where locals come to swim, unwind, and soak in the natural beauty. The water is impossibly clear, the fish dart between your feet, and the calm atmosphere makes it feel like a hidden retreat.

Looking for more ways to explore? Check out our guide to the coolest things to do in and around Cap-Haïtien.

Getting There & Getting Around

Getting to Cap-Haïtien is easier than you might think. Direct flights from Miami and Fort Lauderdale take just two hours, making it a quick escape to Haiti’s northern coast.

Once you’re here, getting around is part of the adventure. Moto taxis are the fastest way to navigate the city’s lively streets, while tap-taps—Haiti’s colorful shared taxis—offer a budget-friendly way to move between neighborhoods. Private taxis are also available, but don’t expect Uber or Lyft—ride-hailing apps don’t operate in Haiti.

Thinking about renting a car? It’s possible, but unless you’re highly experienced with Haitian roads, we strongly recommend hiring a local driver. For a different kind of transport, boat taxis can take you to nearby beaches and islands along the coast.

For more information, see our guides to getting to Haiti and public transportion within Haiti.

Written by the Visit Haiti team.

Published December 2019.

Updated March 2025.

Top things to see in Haiti

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.