Photo: Mikkel Ulriksen

Return to the Motherland

If going back to your ancestral roots is something you value as a black traveler, Haiti should definitely be on your itinerary.

Filmmaker Hans Augustave once shared a quote from his tour guide in Haiti on social media which read, “If every Muslim should go to Mecca once in their life, every Black person should go to Haiti!”. History is forever marked by the fact that Haiti is the first black nation to gain its independence from colonizers in the world, and by doing so, an example was set for other nations to follow. That emancipation set the tone for a wave of black consciousness among slaves around the world and continues to this day to inspire many who attempt to break free from the patterns of dependency and reconnect with their land and culture of origin, specifically people of color.

Many of those living in the Haitian diaspora can relate to feeling like Haiti is a land so close, but ever so far away. Even if you haven’t bought a ticket to visit yet, you know of all the tales of your family’s hometown through the oral history shared by mothers, aunts, and grandmothers surrounding you – but there are gaps that this history cannot bridge.

This is the importance of a homecoming.

Whether you are connected to Haiti through your parents or otherwise, it should be on your list of top 5 places to travel to next for one simple reason: as a descendent of Haitians first, but also as a Black person, your heritage courses through the island. Just like the Year of Return for Ghana and many other West African countries, Haiti can be considered a home away from home.

Photo: Mozart Louis

Why come back?

If you have family still living in Haiti that you keep in touch with, coming to Haiti will quickly show you that phone calls sometimes fall through. There’s nothing like hugging a cousin who always says “Hello!” before passing the phone to his mom, or seeing the uncle all the family stories feature, or getting to know neighbors who saw family leave, but who still remember the days of the past, and miss them dearly. Facing origins means facing home, too.

As any frequent traveler to Haiti will tell you, the experience begins when you get off the plane at the Toussaint Louverture international airport (if you’re landing in Port-au-Prince). From the sudden, warm heat that envelops you when you get off the plane, to the troubadour band playing outside the customs office, everything primes you for the experience of finally making it to the land of your elders.

Reasons to come back will surface all along your trip. You will find them in the sweet, tender, ripe flesh of Batis mangoes, or in the crispy, savory bits of fried pork eaten on late nights out with friends and family, in front of a street food vendor’s kitchen. If you come home during the summer, you’ll have the luxury of experiencing the island’s finest fresh produce, lively events – many of which happen closer to your neighborhood than you think, and peak season for cultural events happening in the capital city. Should you be in Haiti during the winter, reasons to come back will paint themselves in the vivid colors of the sunsets, in the playfulness of children’s faces under Christmas lights in Pétion-Ville, and in the hope that new year’s celebrations offer to everyone on the island.

If you are looking for reasons to come visit Haiti, your best bet is coming to see them for yourself.

Photo: Franck Fontain

What does Haiti offer?

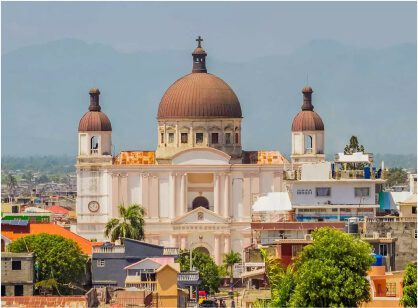

Besides its beautiful beaches and breath-taking hikes, every inch of Haiti is an open window on the history that has affected black lives around the world. If going back to your ancestral roots is something you value as a black traveler, Haiti should definitely be on your itinerary.

The celebration of the black identity can be found in historic sites such as Citadelle Laferrière or any other fort, as well as in the food, the dances, the cultural celebrations, music, and even the language! Haiti holds one of the most unique blends of African heritage and contemporary Latin American and Caribbean tastes and cultures.

Photo: Verdy Verna

When to travel?

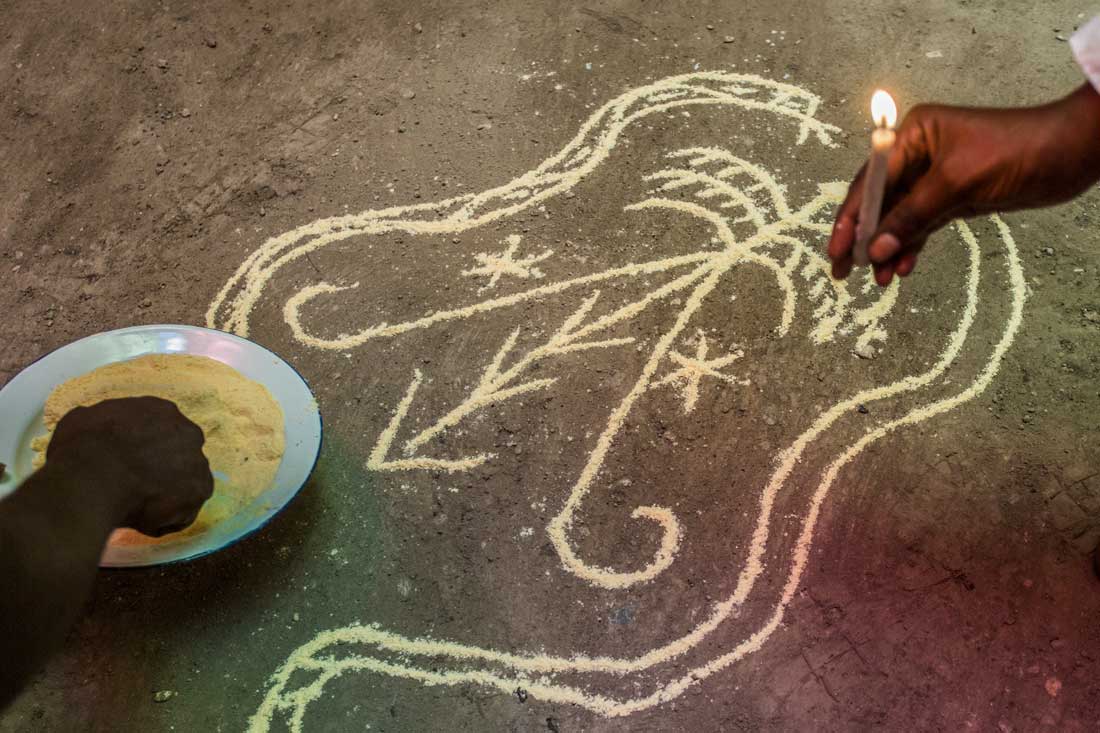

If you want to experience Haiti as the true home away from home that it can be, February is a time of the year when rhythm and spices are flowing all over the island. Carnival is a very Carribean affair, but to experience it in Haiti is a double-whammy; every Sunday, for about a month, then very intensely for 3 days, Haiti becomes a bubbling hub of celebration of Haitian music, dances, and colors. If one looks and experiences more deeply though, it’s an important period for the Vodou religion and community rooted in Benin and other West African countries.

During Kanaval and more specifically the pre-carnival period, those who practice or follow the religion take their celebrations to the streets under the form of raras and often are mixed up with regular citizens simply celebrating Kanaval. Rara is a dance and ceremonial form of expression rooted in Haitian identity, its presence in Vodou has served many historical moments such as the Bois Caïman Vodou ceremony which was pivotal in the declaration of Haitian independence.

Rara can also be experienced in November (hint: get away from the cold!) which is a culturally and historically rich month for Haiti as well. On November 2nd, the day of the dead is celebrated in both the Catholic community and the Vodou community meaning that there is a larger presence and visibility for these groups in the streets and in cemeteries. November also houses the anniversary of the Battle of Vertières which was pivotal to the Haitian Revolution.

There is something to be said about finally knowing and understanding where one is from. Haiti prides itself on being one of the warmest islands of the Caribbean, both in temperature, and in temperament. There are always the open arms of family, friends, and hosts who want nothing more than to share their favorite parts of home with you. If you considered planning a trip to Ghana, Nigeria or any other African country, consider starting with one of the most afro-affirmative Carribean countries in your journey to self-discovery. Depending on where you’re coming from, getting to Haiti can be more accessible or affordable, but regardless, it will always be an essential experience in the black traveler’s journey.

Written by Kira Paulemon.

Published September 2020

Explore Haiti’s Art & Culture

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.