Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

The Cordasco House (Villa Miramar)

The Cordasco House is one of Haiti’s most iconic gothic gingerbread mansions. The House has been closed to the public since the 90s, but Visit Haiti was able to take a sneak peek inside. Take a look at our exclusive virtual tour of this national treasure.

First impressions

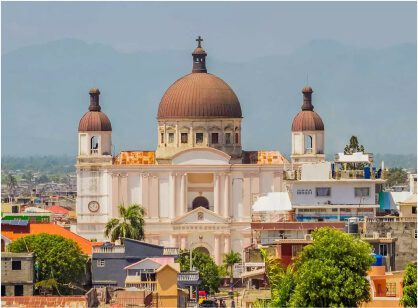

If you drive into Port-au-Prince from the south-east (maybe after a weekend in Jacmel) you can’t miss the charismatic Cordasco House. At a fork in the road where you turn right to continue into PAP proper, rising above you is the yellow, orange, and creamy-brown heights of one of Haiti’s most photogenic Gingerbread mansions. This is the Cordasco House, also known as Maison Cordasco, Villa Miramar, and “Le Petit Trianon” in honour of the palace of the same name in Versailles. In Haitian Kreyòl, Cordasco House is affectionately known as Ti Trianon.

As a child, I remember sitting in the back of a pickup truck coming back from Jacmel and looking up in awe at the latticework, turrets, and high, rounded towers. The high-walled gardens overflowed with the tops of frangipani trees, their aromatic waxy flowers heavy. The house was as imposing as any fairytale castle I could conjure, and my childhood self wondered if Haiti’s own Rapunzel lived up in those towers.

Gingerbread houses are ornate turn-of-the-century buildings unique to Haiti. Like their edible namesake, Gingerbreads are famous for steep roofs and ornate details highlighted in vibrant, contrasting colours. They are architecturally fascinating for a number of reasons – not least because they’ve proven to be surprisingly resistant to earthquakes.

In 2020, I was invited by a colleague in the arts to take a private tour of Cordasco house, and I finally got to go through the tall gates I had been gazing at in wonder since childhood.

Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

Take a peek inside Cordasco House

At the gates, a stone-faced guard greets me with a twinkle in his eye – one part artisan, one part soldier, I soon discover – and swings open the gate. A long, wide driveway, lined by flowering trees, winds toward the four-story turreted mansion. Large, heavy stone vases are embedded in the entryway masonry, flanking the double staircase leading to the main door.

Cordasco House and many others like it were rapidly built in Port-au-Prince starting in the 1860s, as Port-au-Prince’s economic and industrial growth skyrocketed. At that time, as Haiti’s only port open to foreign trade, it was the epicenter of commerce on the island. A new bourgeoisie class of affluent traders, businesspeople, and educated professionals flourished. Opportunity was everywhere, and as the city’s population grew in tandem with its economy, the newly wealthy class migrated out of the chaotic downtown core to the evergreen eastern hillsides of Turgeau, Bois Verna, and Pacot with gorgeous views of the bay. This district is where you’ll find many of the attractions on our self-guided gingerbread tour.

Villa Miramar, the name given to the house by its original owners, can still be seen traced in wrought iron filigree above the main entrance that arches above the grand staircase. As appreciation for the gingerbread style grew, the house increasingly became known as maison Cordasco, after one of the most famous architects of the style.

There’s two theories on who designed and built the Cordasco House. One theory claims the house was built by Fioravante Cordasco, an Italian-born architect active in Haiti until the mid-twentieth century, and an integral part of the gingerbread movement. Although the nickname of “the Cordasco house” lends weight to Cordasco theory, a joint project by Haitian art collective FOKAL and Columbia University writes that the house was actually built by Parisian-trained Haitian architect Joseph-Eugène Maximilien. According to FOKAL, Maximilien built the house in 1914 for the lady Ewald Clara Gauthier.

Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

The guard waves me to drive my car past the main house, to where a second, separate building stands. A series of smaller houses stretches behind the mansion’s back, many of them with ornate balconies and gingerbread trim. Towering trees, manicured gardens and pools complete the picture.

The gingerbread architectural style in which the Cordasco House is built is truly creole, blending together foreign influences with local materials in an ornamental way. For example, Haitian gingerbread houses adopt 1830s Victorian “picturesque” features like intricate trim that resembles lace, but execute it with locally available and affordable elements like timber-slatted siding. The classic flamboyant colors of Victorian houses are intensified to neon.

Here in Haiti, the vaulted ceilings sometimes seen in Victorian architecture are an essential feature, improving air circulation in the sultry eternal summer of the Caribbean. To provide shade from the Haitian sun and accommodate the need for daily meeting space, where much of Haitian life takes place, gingerbread houses have wide galleries and porches, integrated into the faux-Victorian aesthetic with intricately adorned latticework.

Climbing up the main steps, I enter a high-ceilinged ante-chamber which opens out onto a three-story winding wooden staircase, rising up, up, up into the rafters. On either side are the principle rooms of the ground floor, framed by intricately-carved doorways.

Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

In the 1970s and 80s, the Cordasco House rose to new fame in the city as a tea house and fashionable boutique under the name Le Petit Trianon, and many of Haiti’s society ladies recall stories of lunching in these airy rooms.

The early 1990s saw the gingerbread house become a home once again, as a private residence to members of the Hudicourt family. One former resident, Lorraine Hudicourt, currently the owner-operator of La Lorraine Boutique Hotel, recalls fond memories of climbing the frangipani flower trees in the front yard in her youth, and playing hide and seek in the fourth-floor attic space with her many sisters and tribe of cousins. In those days, the gates were often open all day as children and cousins came and went, bringing life, laughter and mischief to all corners of the vast property. Housekeepers slept in the sprawling staff quarters at the top of the property, themselves equivalent in size to three Haitian middle-class houses.

Indicating where I should place my step due to earthquake damage, the groundskeeper leads me up the staircase to the second and third floors. Each doorway, each moulding, is intricately carved. Green granite countertops and Portugese tiles decorate the bathrooms. The slanted floors bely the age of this grand old lady, but do nothing to diminish her dignity or grandeur.

Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

The Cordasco House survived the 2010 earthquake, but not without some bruising. The walls suffered several large cracks, and the three-story spiraling staircase that rises up through the house’s center was destabilized. Fortunately, though much of Haiti’s capital had been levelled by the disaster, the Cordasco House’s foundations were undamaged.

The Cordasco house’s resilience is part of a surprising trend. U.S. conservation experts discovered that only five percent of the estimated 300,000 gingerbread houses of Haiti had partially or fully collapsed due to the earthquake, in contrast to forty percent of all other structures, most of which had been considered to be in better condition. The Wall Street Journal suggests that Haiti’s Gingerbread architecture could serve as a model for seismic-resistant structures in the future.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, the owners opened up “Ti Trianon” as an improvised hospital for earthquake victims, run by Medecins Sans Frontieres. Part of the house continued to be rented out to NGOs for several years, and was fitted with impromptu walls to delineate offices and cubicles. By 2018 though, many international charities had largely pulled out of Port-au-Prince with their budgets in tow, and office rental in the Cordasco House came to a halt. For two years, only the trusty guardian graced the dozens of rooms, protecting this historic property.

In early 2020, the owners threw open the shutters to sunlight once more, investing in renovations. The neighbourhood of Pacot became a flurry of movement as gallons of fresh white paint coated the Cordasco House’s interior and new scaffolding was erected against the famous facade, ready to usher in another new era of the house’s rich history.

By the time I step out onto the uppermost balcony, an orange and pink sunset is unfurling over the bay of Port-au-Prince.

Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

Cordasco House is currently not open to the public, but you can see it from the corner of Rue Pacot and Avenue N in the area of Pacot, Port-au-Prince.

Want to see inside a gingerbread house? Here are my two top picks nearby:

Gingerbread Restaurant: For those looking for a fabulous gingerbread house as a backdrop for photos or a video shoot, we encourage you to discover this nearby gingerbread mansion of equivalent grandeur. Known for great cocktail hours by the pool, Gingerbread Restaurant also does great pizza and salads, and the herring and cod croquettes are out of this world.

Open to the public, Gingerbread Restaurant is located on 22 Rue 3, Pacot. Look for the light blue gate. Open 11am to 10pm Monday through Saturday. Closed Sundays.

Hôtel Villa Thérèse: This three-story gingerbread mansion is distinctly different from most of the gingerbread houses, but its pink turrets and ornate masonry, painted in soft yellows and vibrant blues, clearly draw on the same tradition. Villa Therese operates as a boutique hotel, but you don’t need to book a stay to see inside – anyone can visit the restaurant, open 6:30am to 9:30pm.

Hôtel Villa Thérèse is at 13 Rue Leon Nau Nerette, Petion-Ville.

For a list of gingerbread houses open to the public, check out our guide to gingerbread houses in Haiti.

Photo: Lëa-Kim Châteauneuf / Wikimedia Commons

Written by Emily Bauman.

Published December 2021

Find The Cordasco House

External Links

Read more about Haitian gingerbread houses

Find out more about Haitian architecture

The Best Hotels in Haiti

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.