Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

Fèt Gede: A celebration of Life on the Day of the Dead

See the photos from a Fête Gédé celebration in Gonaïves and discover the most anticipated festival in Haitian culture! A celebration of Life on the Day of the Dead for both Christians and practitioners of Haitian Vodou.

Every November in Haiti, there are festivities held throughout the month that, for an outsider, might seem, well, quite strange! In particular, the Fête Gede (Day of the Dead) and All Saint’s Day involve unsettling processions to the cemetery of each town around the country.

The crowd that gathers is a varied group, comprising people who are simply curious as well as people of all different faiths, including Hatian Vodou. They join together to walk to the main cemetery in each town, all the while following the unique spectacle that the procession offers. And what is this spectacle, exactly? Practitioners of Vodou taken over by the Gede, the spirits for whom these stunning celebrations in Haiti are held.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

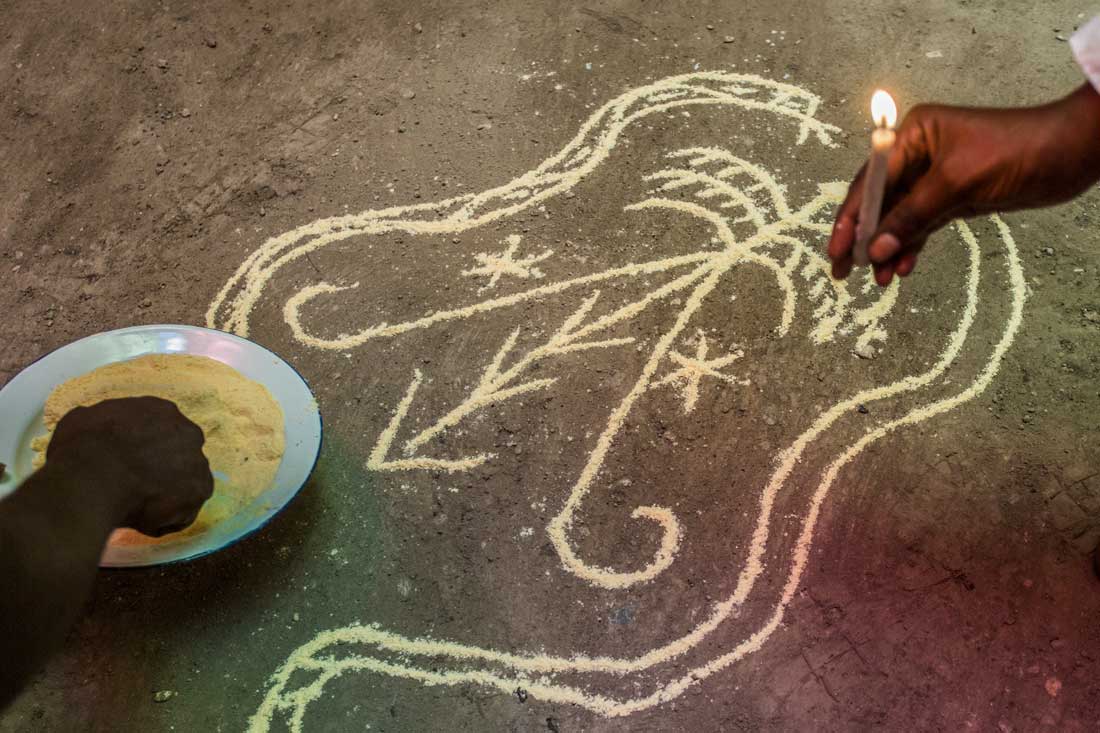

In Vodou spirituality, the Gede are the spirits of the dead. They are responsible for accompanying the dead on the path toward the other world, but also of watching over the living. They thus constitute the bridge between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Two major Gede deities in the Haitian Vodou pantheon are Baron Samedi and Grann Brigitte.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

Those possessed by the gede spirits set the festival’s tone, which is truly carnivalesque. You might hear some rough language, see some dirty dancing, and witness other extravagant performances. All of these provide plenty of entertainment for the more docile crowd that follows along.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

Fueled by alcohol, as well as hot pepper-based infusions that they sprinkle on their bodies, the procession heads toward the main cemetery. Overtaken by the spirits of the dead, the possessed swear and carry out quite a remarkable performance.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

The spectacle of the procession attracts quite a crowd, and the possessed are easily recognizable due to the ritual colors of Baron Samedi that they wear (white, black, and purple). Some even cover themselves entirely with white powder or draw gloomy scenes on their bodies. Others choose to wear the preferred attire of Baron Samedi, which includes a black hat, monocle, and cane. Altogether, this creates a true Carnival of the Dead that happens every year in Haitian cemeteries.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

This Festival of the Dead, which comprises rituals and dances all November long, testifies to the intimate link that exists between the world of the living and the world of the dead in Vodou spirituality. For practitioners of Vodou, Fête Gede is really more like a celebration of life. The gede spirits who return via their hosts during possession can attest to this way of thinking. They are brought to life by joy and are spirits who love to laugh, dance, and have fun.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

All of these wild performances have just one objective: to amuse. The festival is not a moment for tears or regrets but rather a time to honor the memory of the departed. Part of this involves preparing for the festival by cleaning the cemeteries and restoring the tombs.

Those who have sailed for “the land without a hat” — a Haitian expression that means the “beyond,” because no one is buried with their hat — remain present in daily life and are nonetheless celebrated as they should be during this festival given in their honor. In Vodou spirituality, those who have set sail for the world of the dead maintain an important role in everyday life. The spirits of those who have passed on, bearing the name Gede, are respected as guardians, advisors, or vengeful spirits by those who remain.

The Fête Gede festival in Haiti is somewhat similar to the Day of the Dead as practiced in other parts of the world (e.g. Dia de los Muertos). The difference, however, lies in the place that the dead occupy in Vodou belief and in the syncretism underlying the various beliefs that Haitians hold.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

As a legacy of ancestral African traditions, Vodou reserves an important place for those who have departed this world for the next. In the procession of the Gede, different people portray different divinities, including Baron Samedi, Baron Lacroix, Baron Criminel, Grann Brigitte, and all the other Gede spirits. Much more than simple guardians of death and graveyards, the Gede are also guardians of life.

As such, the celebration of Fèt Gede is not just a celebration to commemorate the dead, but a celebration where the dead can take part by way of possession in the form of Gede spirits.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

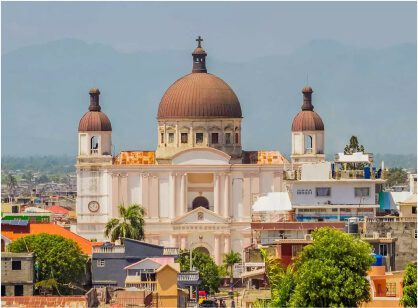

At the main cemetery in Port-au-Prince, where the biggest iteration of this festival is held each year, Catholics come to pray for the souls of their deceased at the small chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows, Protestants come to gather at the graves of their lost loved ones, and practitioners of Vodou come for the largest celebration of the Fête Gede festival in all of Haiti.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

The festival is at the very crossroads of Haiti’s religious syncretism, with Catholics and Protestants joining the procession to the cemeteries, all worshiping differently but each bearing the same thoughts for the departed, thoughts colored by the beliefs on which these extraordinary celebrations are based.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

Even if Fèt Gede is held on and around All Saint’s Day and the Day of the Dead, it’s a much different celebration than ones that you might see elsewhere. It’s a true moment of communion between the dead and the living, the latter of whom brings coffee, roasted corn, cassava, clairin (rum), or the favorite dish of the lost loved one.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

One might even be tempted to say that Fèt Gede is much more than a simple set of practices based on certain beliefs about death — rather, it constitutes a genuine philosophy of life, a life that must be lived like a carnival. If we enjoy every moment, it won’t be the Gede who contradict us!

Written by Costaguinov Baptiste.

Published in October 2022.

Explore Haitian Vodou & Spiritualism

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.