Photo: Franck Fontain

Dondon grottoes

Located in the mountains of northern Haiti, Dondon has been settled since pre-colonial times when Haiti’s indigenous Taíno peoples lived there. This little corner of Haiti attracts a lot of tourists, and the main drawcard for visitors is the opportunity to explore the stunning system of grottoes nearby.

Photo: Franck Fontain

The grottoes

Dondon’s spectacular cave system has ten separate grottoes. Some are easy to access and have a given name: Ladies’ Vault, Marc-Antoine grotto, Smoke Vault, Cadelia Vault, Saint Martin Vault, Minguet Vault and Michel grotto, all named because of their individual history.

Some of these caves were Taíno cult locations during the pre-colombian period, where the Taínos would come to pray to their gods. One of the gods prayed to in times of drought is still visible on the walls of the grotto, and in post-colonial times is venerated by vodouwizan as an important figure within vodou. The other grottoes remain unnamed, their histories steeped in mystery.

Guided tours

Many Dondon area locals – young and old – are happy to jump into the role of guide for the grottoes. Some have learned by heart formulas in French and English, which can make for charming – if confusing – conversation.

Experienced and impromptu guides will be more than happy to help you discover the best spots, hidden petroglyphs and the history infusing these grottoes – some of this history only survives as stories handed down from generation to generation, so you won’t find it anywhere else.

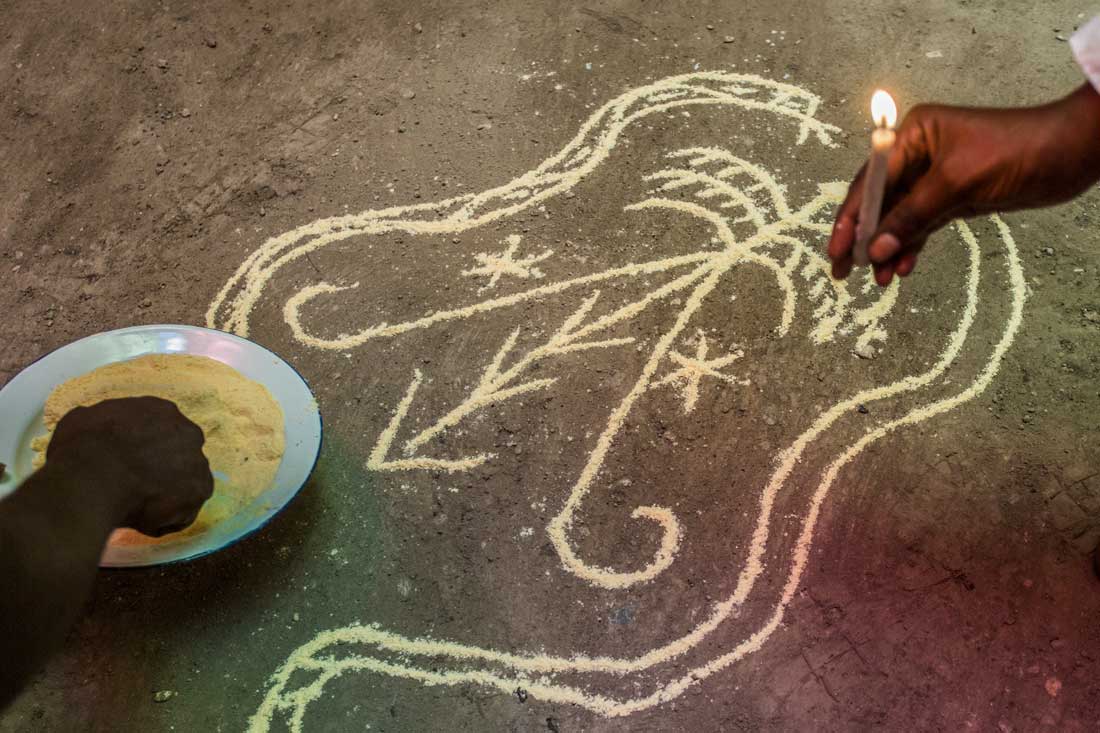

Photo: Anton Lau

Festivals in Dondon

Every town in Haiti has its own patron saint festival. In Dondon, pilgrims come from far and wide to celebrate Saint Martin of Tours. Some come here to party, others come as tourists to observe, but most are here to honor the Vodou divinities, the lwa believed to live here. The patron saint festival of Saint Martin of Tours happens in Dondon on November 9 – 11, but party preparations start on November 7. For five days, crowds filter into Dondon to savor kleren, eat delicious griot, and dance to troubadour music from morning ‘til night.

There is also the Dondon Festival, held from July 18 to 23. This festival is about Dondon itself rather than lwa, and draws vacationers who come to take advantage of the great swimming spots in nearby rivers, go on excursions and participate in the conferences that take place for the occasion.

What else is nearby?

Dondon is close to the UNESCO World Heritage Sans-Souci Palace and Citadelle Laferrière, which locals call the eighth wonder of the world. A visit to both sites is considered essential for any visit to Haiti, and the journey there is well-worth the effort.

Fort Moïse, on top of the Saint Martin Vault, is also close by. Other attractions include the Kota waterfall and the historical Vincent Ogé residence. The on-site coffee co-op at the residence is a great place to taste the very particular flavor of Haitian coffee.

Photo: Franck Fontain

Getting to the Dondon grottoes

Dondon is located in the north of Haiti, about a two hour drive south of Cap-Haïtien. The journey to Dondon will take you over roads that are winding and can be pretty rough in places. On paper (or GPS), the route through the town of Saint-Michel might look good, but that road serves up more adventure than most travellers are looking for, and we don’t recommended it. The best way to get to Dondon we’ve found is this one:

From Port-au-Prince, drive out of the capital towards Cap-Haïtien via Route Nationale #1. The road to Cap-Haïtien makes up the longest chunk of the drive, but its recent completion makes it a comfortable trip, not to mention a scenic one, with many towns to stop in along the way, each with their own character. Once in Cap-Haïtien, continue towards the town of Milot. Make a left after you pass Rivière du Nord, and in another hour or so you’ll arrive at Dondon.

There’s no formal fee to see the caves but you’ll need to hire a (formal or informal) guide. Remember to bring food and drinks with you for the trip as there’s no guarantee you’ll find anything on site, although Lakou Lakay is a great place to stop for lunch if you’re travelling via Milot.

Written by Jean Fils and translated by Kelly Paulemon.

Published April 2020

Find the Dondon grottoes

External Links

Learn more about Dondon

Looking for some cool things to do?

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.