Photo: Franck Fontain

Fèt Gede – the Haitian Day of the Dead

Fèt Gede – the Haitian Day of the Dead – is an annual tradition when practitioners of vodou parade through the streets, possessed by the spirits of the dead (gede)

Every year, on November 1 and 2, Haiti becomes the stage for a unique celebration: Fèt Gede, the “Festival of the Dead”. Much like the Day of the Dead practiced in Mexico and by Latin communities in the US, Fèt Gede is a way to pay respects to loved ones who have passed on.

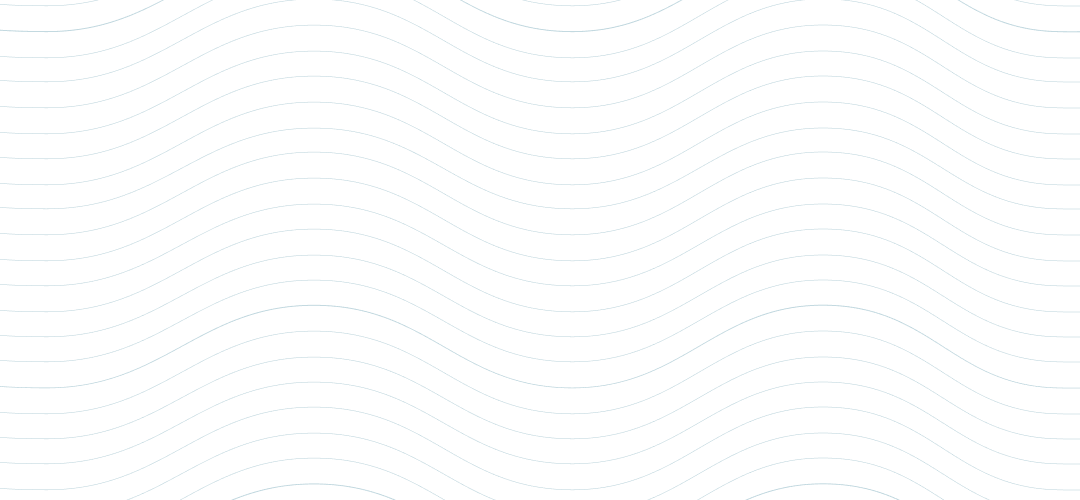

In Haiti, each religion celebrates this differently: Catholics meet at church for a mass dedicated to the deceased, and Protestants come together too — but adherents of one of the country’s state religions — vodou — celebrate their deceased in a much more festive way. Although it overlaps with the concept and calendar space of Christian All Souls Day, Fête Gede traces its origins to African ancestral traditions, preserved across oceans and centuries in modern-day Haiti.

Gede shows are notoriously loud and extravagant, and can be seen nearly everywhere across Haiti, with Vodou practitioners dressed elaborately to represent the subset of lwa or loa — “spirits” — called gede — “the dead”. Gede may be invisible for the rest of the year, but during Fèt Gede, the dead definitely do not go unnoticed!

See more photos from a Fèt Gede celebration in Gonaîves here!

Fèt Gede celebrations

Photo: Franck Fontain

Vodou, lwa and gede

Vodou is a prominent feature of Haitian culture, and as a religion it has many practitioners — called vodouwizan — spread across the country. The religious syncretism between vodou and christianity has historically made it difficult to make an official estimate of numbers of practitioners, since most people who practice Haitian vodou to some extent also identify with a Christian denomination, but unofficial estimates suggest as much as 50% of Haitians practice vodou. For these vodouwizan, Fèt Gede is an important occasion to honor the gede.

But what are the gede exactly?

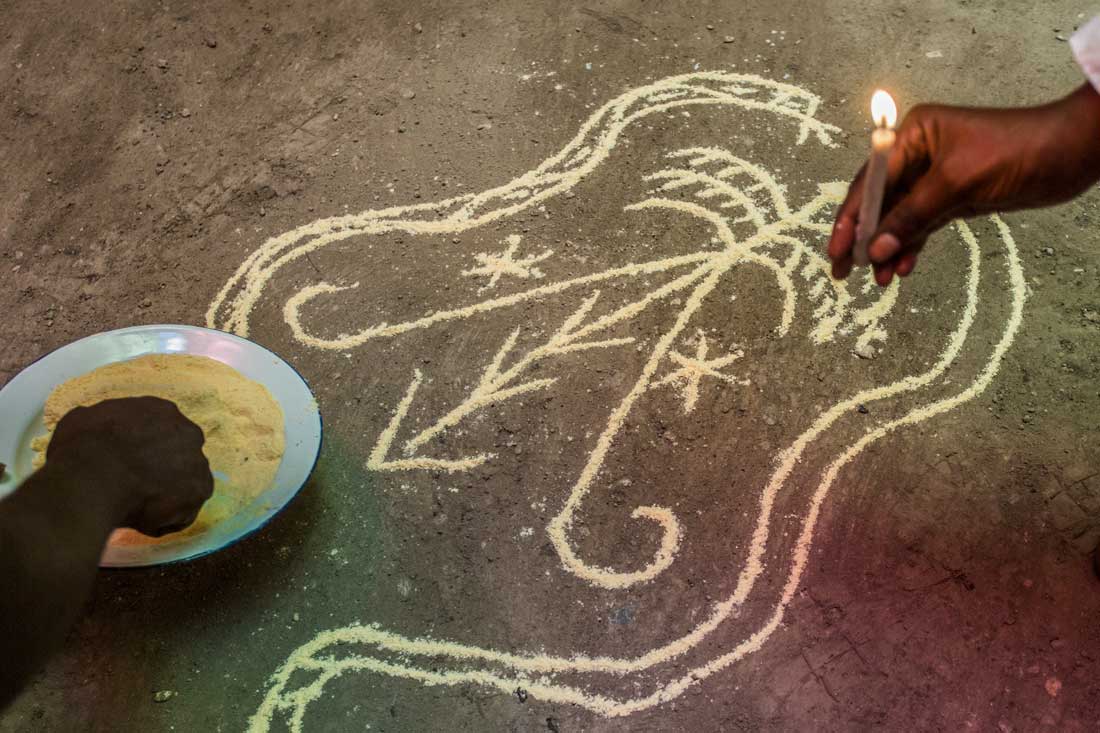

Every vodouwizan has their own gede. It’s either a close friend or a relative – the gede is the reincarnation of a loved one who has come from the afterlife to live in the body of the vodouwizan who called upon them. But not every ancestor is venerated as a gede. For the dead to become a gede, the vodouwizan must, through a Vodou ceremony, contact the deceased and transform them into a gede, which they can then invoke as they see fit.

According to vodou, by becoming a gede, the deceased are transformed from being simply a human soul that has passed on into a lwa, and this lwa generally has a name that begins with gede, for example, gede loray, with loray meaning “thunder.” Sometimes a relative who served a gede dies, and another vodouwizan decides to take up servitude of that same gede.

Party in the cemetary

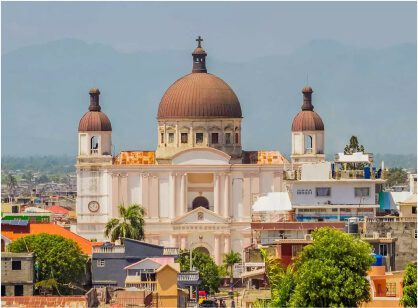

During gede celebrations, the streets of every city are full of vodouwizan. On November 1 and 2, vodouwizan come together to around cemeteries to make devotions, perform precise rituals, and to generally honor the deceased.

Every cemetery on the island is overrun by vodouwizan – some possessed by gede, and others not. Those who are possessed are easily recognizable by their attire: dressed in white, black, and purple, their faces covered in white powder and black sunglasses, a walking stick in hand, and the indispensable bottle filled with alcohol and hot peppers (especially kleren and a type of habanero called goat pepper). The gede love hot peppers, and from time to time, in the middle of the street, they pour the pepper-infused alcohol all over their bodies, and particularly on their genitals, writhing and mimicking erotic postures and scenes, much to the delight of spectators.

Possessed by the gede lwa, these men and women cover several miles on foot while dancing, their waists leading their every movement. Following an unspoken instruction, they all share a single final destination: the cemetery. Once at the cemetery, the boisterous spectacle continues with loud singing, erotic dancing, and bodies drenched in spicy substances. Other vodouwizan who have come to visit their deceased relatives and friends take some time to pour coffee and grilled corn on their graves, and talk with the relative or close friend.

But first, paraders must obtain permission to enter the cemetery at the ceremonial grave of the “first man”, Bawon Samdi, and the first woman, Manman Brijit. The gede are a very large family; Bawon Samdi represents the father, Manman Brijit the mother, and they’re followed by Bawon Kriminèl, Gede Nibo, Gede Loray, Brave Gede, and Gede Zanrenyen, who together form an escort for all gede.

Bawon Samdi (/Samedi), also known as Papa Gede, presides over the festivities. Papa Gede’s colors are black, white and purple, and he is often characterized smoking cigars, wearing a top hat and sunglasses – frequently with only one lens. Some say this is because Bawon Samdi sees both worlds, which gives him an uncanny resemblance to the one-eyed god Odin of Nordic mythology, who also tread the path between the dead and the living.

Photo: Kolektif 2 Dimansyon

How to get involved

Each November heralds the sacred and spectacular celebration that is Fèt Gede – a raucous, bawdy, fiery festival that embodies many of the essential elements of Haitian culture, all splashed with bright paint, spicy food, strong drinks, and the rhythm of people’s feet on the pavement.

Fet Gede rituals are held throughout November but are concentrated on November 1 and 2. The biggest and brashest parade happens in Port-au-Prince at The Grand Cemetery, or ‘Grand Cimetière’. If you’re travelling by car, be prepared for the enormous crowds that make it impossible to get near the cemetery – you won’t find a place to park, but a chauffeur should be able to get close enough to at least stop and let you out. Entrance is through the main gates, which reads “Souviens-Toi Que Tu Es Poussiere” (“remember you are dust”).

Written by Jean Fils and translated by Kelly Paulemon.

Published October 2019

Explore Haitian Vodou & Spiritualism

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.