Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

11 Haitian Cultural Traditions You Didn’t Know About

The Essential Haitian Traditions to Know

If you already know a little about Haiti, then you likely have an idea about our magnificent country, located on the enchanting island of Hispaniola that we share with the Dominican Republic. It’s possible, however, that you have yet to hear about some of the most unique Haitian cultural traditions only known to locals.

To satisfy your curiosity, we’ve rounded up a selection of our oldest traditions, ranging from the daily life in our rural communities to the hubbub of our cities and rich culinary culture.

Photo: Anton Lau

1. “Krik-Krak”

Any true Haitian knows that the exclamation “krik?” always proceeds with an excellent “krak,” or story, as telling tales is an integral part of Haiti’s cultural traditions. Whether under an arbor drinking lemongrass tea with cinnamon or in the comfort of a warm room, the youngest gather around the oldest to tell their tales of yesteryear.

If you want to catch the attention of a Haitian friend, take every opportunity to throw out a “krik?” and they will invariably respond with a “krak.” But your story better be a good one!

Sounds interesting, doesn’t it? Get the backstory to this unique tradition and discover the impact of krik-krak in Haitian culture. Also, for an excellent read, the book Krik? Krak! is a compilation of fascinating Haitian tales by Edwidge Danticat, one of the most famous Haitian women authors to date.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

2. Konbit

If you pass through some rural regions in Haiti during the tilling season, don’t be surprised to find all the villagers working together or on each other’s lands. This form of social organization in our rural societies is an essential part of our culture and one of the oldest Haitian traditions that continue to this day.

While the men happily handle their kouto digo (hatchet), and machetes to unearth and work the land before its next sowing, women prepare the meals. Moreover, the word “konbit” in Haitian Creole has come into use to refer to living in harmony and the neighborly practices that are unique to the Haitian community.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

3. Lakou

Imagine living in a homeland within another, where each individual forms an integral part of a larger society devoted to a greater good. In Haiti, such a place is known as a lakou. It’s typical to see Haitian families sharing common spaces around their central family units.

The lakou serves as an educational cocoon in which the youngest members can learn about sharing and living in neighborly harmony from their elders. Those who grow up in the commune have a responsibility to one day return to honor their family, seek wise advice, and publicly apologize to the Vodou spirits or loas that may have been offended.

Many Haitian rural communities rely on the social organization that lakou provide to advance in everyday living – and not only do they till the ground together but also share and practice their belief in Haitian Vodou. The worship of spirits is deeply entrenched in the lakou, and well-known lakou like Souvans, Soukri, and Badio maintain this cultural tradition unique to Haiti.

Photo: Anton Lau

4. Beny chans

It might seem strange from the looks of it initially, but if you happen to come across a large water bowl of mixed herbs and leaves while traveling through Haiti, then you’ve encountered a “beny chans.” Traditionally an herbal shower for women after giving birth, it is also considered a potion for good luck, finding a soulmate, or even protection during a life-changing trip.

If you didn’t grow up in Haiti, you might be wary about dipping your hands in this unusual mixture. Still, for locals, it’s all part of the unique Haitian culture – so much so that it wouldn’t be surprising for a native living abroad to return to Haiti to receive this sacred anointment on New Year’s eve.

Feeling adventurous? Go and give it a try. But don’t forget to tap into your African-Caribbean roots with our guide on returning to the motherland.

Photo: Pierre Michel Jean

5. Vodou ceremony and dance

Here’s one of the Haitian cultural traditions that will undoubtedly arouse your curiosity. Forget about the mainstream concept of a group of bloodthirsty Satanists gathering at a run-down Gothic-style church – this is Hollywood stereotyping at its best. Instead, think of an authentic spiritual experience where members enter a trance-like state in alignment with powerful spiritual entities.

Haitian culture isn’t the only one that has Vodou as a religious practice, with similar rituals actively performed in places like the “Deep South” in Louisiana or the insular African nation of Benin. In countries such as Brazil and Cuba, the practice of Santeria is still common in many communities. The Haitian Vodou tradition, however, involves elements from years of syncretism, resulting in a blend of African, Christian, and Taíno spiritual traditions.

Vodou is a strong cultural tradition in the Haitian collective imagination—and it’s present in Haitian paintings, music, dances, and literature. More than simply religion or spirituality, Vodou is an intangible patrimony that all Haitians share, whether they consider themselves a true practitioner or not.

Ready for an experience of your own? Find out how to attend a Vodou ceremony in Haiti.

Photo: Franck Fontain

6. Fèt Gede

The dead occupy a place of central importance in Haitian daily life, and honoring them constitutes one of the most sacred cultural traditions. To do this, the entire month of November is consecrated each year to ceremonies aimed at appeasing the dead and communicating with them. The spirits that reign over the world of the dead in the Haitian Vodou pantheon are Bawon Samdi and Grann Brigitte.

The Gédé symbolizes the spirits of those who have passed into the other world. During the ceremonies organized in their honor, they return to bring joy to the people with their frenzied dancing and salacious speech.

Every Haitian day of the dead celebration is packed with an aura of excitement and mysticism, which you can see for yourself in this photo journal from a Fèt Gede celebration in Gonaîves.

Photo: Franck Fontain

7. Rara

Not all Haitian cultural traditions have origins as dark as those about death. In fact, some of them are rather joyous, and the Rara is a perfect example. These groups that march on foot along the streets during pre-Carnaval weekends and the Easter period constitute one of Haiti’s best-known cultural practices.

These spirited groups of bons vivants play various instruments, such as bamboo, the vaccine, cymbals, and sometimes even trumpets and other brass instruments. Their repertoire can run from parodies of popular songs to original songs and those written for special occasions.

Each group is preceded by a man who carries a flag, a woman who wears the group’s colors, and young girls who start the procession. Following are musicians and the rest of the good-natured group that dances along to the sound of the music.

Now, the practice of Rara isn’t only particular to Haiti; other Caribbean nations like Cuba and the Dominican Republic, where it is known as Gaga, have adopted this cultural tradition from Haiti.

Get the true origins behind the Rara tradition of Haiti and join the celebration!

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

8. Lansèt kòd

If you visit Haiti during the Carnival period, you’ll undoubtedly have the chance to witness one of the most unforgettable cultural traditions: the famous procession of the Lansèt Kòd. Some Haitians will tell you that they were traumatized by it as children. These groups that flood the streets of towns such as Jacmel, Jérémie, or Cap-Haïtien on pre-Carnival Sundays have more than what it takes to impress.

Wearing bull horns on their heads and whips in hand, these men with rippling muscles and bare chests fill up the streets while covered entirely in black paint. Yes, you read that right—they are completely covered with a blacker-than-black substance that will surely make you think of crude oil. Throughout the Carnival procession, they’ll offer up a performance that will remain ingrained in your memory for some time.

Learn more about the Lansèt kòd tradition here!

Photo: Franck Fontain

9. Carnival

The Haitian carnival is one of the most widely recognized in the Caribbean. The one hosted in Jacmel has been decreed a national festival due to its artistic allure, attracting numerous tourists every year. It is a brightly colored cultural manifestation where you’ll see Haitian artisans’ talent displayed in themes reminiscent of flora and fauna of the country.

This popular celebration is not only an occasion for artists and artisans to display their talents or attract visitors – but it’s also a means for the population to express their problems with the powers that be. It’s a celebration where all levels of society come together without embarrassment or worrying about societal barriers.

If you’re looking to be part of the festivities this February, then you’d better be prepared to party like a Haitian at Jacmel Carnaval.

Photo: Franck Fontain

10. Soup Joumou

If you visit any Haitian family on New Year’s Day, you’ll be pleasantly surprised by a culinary practice as old as Haiti: the traditional Soup Joumou preparation. So forget about your desire to eat anything else, and let our succulent soup seduce your tastebuds.

Prepared from a giraumont (turban squash) base, where the soup gets its name -as well as vegetables and tubers – this dish is a staple in all Haitian households on New Year’s Day. Don’t be surprised to see people incorporating Soup Joumou with every meal served during the entire celebration. It’s just that good.

This tradition hearkens back to January 1st, 1804, when the young nation chose this delicious dish – until then only reserved for the colonizers and special guests – to celebrate their freshly acquired liberty.

Want to find out what makes Soup Joumou so unique? Pick up on some of the history behind the dish, and learn the basics of preparing the best Soup Joumou.

Photo: Franck Fontain

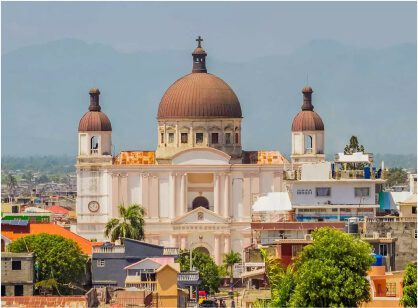

11. Fête champêtre

Every city in Haiti has its own patron Saint to which the inhabitants turn to confess their troubles and joys or make special petitions. These cultural celebrations of the patron saints, also called fête champêtres, are on another level.

Regardless of their religious beliefs, locals from other provincial towns, as well as a crowd of curious onlookers and tourists, head toward the capital cities from each village to celebrate the feast dedicated to the patron saint.

Along with religious pilgrims, you also have the partygoers who are only there to enjoy the festival following the Grand Mass of the local parish. Among the most popular fêtes champêtres in Haiti are the celebrations of Notre Dame of Mount Carmel in Saut d’Eau and Notre Dame in Petit Goâve.

Gather with the locals and go on a pilgrimage to Saut d’Eau, whether for spiritual reasons or just to celebrate and party hard with the crowd.

Written by Costaguinov Baptiste.

Published December 2022.

Explore Haiti’s Art & Culture

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.