Photo: Franck Fontain

Your Ultimate Guide to Carnival in Haiti

With the Haitian Carnival season officially upon us, we’ve drawn up the ultimate guide to the sights, sounds, and flavors not to miss!

Carnival in Haiti is not just a festival, it’s a cultural institution that runs deep in the veins of its people. For Haitians, music is a way of life and during Carnival, it’s like the whole country comes alive in a rainbow of colors, sounds, and rhythms.

But it’s not just about the party – Carnival is a transformative experience that shakes things up and inspires change.

So, read on to learn about what makes Carnival in Haiti so special, and who knows, maybe even plan your own trip to join the celebration!

Photo: Franck Fontain

A brief History of Carnival in Haiti

Let’s start from the beginning; the tradition of the Carnival (or kanaval as it’s written in Haitian Creole) in Haiti started during the colonial period in the bigger cities such as Port-au-Prince, Cap-Haïtien, and Jacmel. At that time, the enslaved people were not allowed to participate. Slave owners wanted to deprive the people of as much as possible, particularly things associated with the lifestyle of Haiti’s white, slave-owning elite.

But the enslaved people staged their own mini-carnivals in their backyards and areas. With costumes made of rags and their skin painted with ashes and grease they imitated and ridiculed the slavemasters. This practice gave birth to one of the country’s oldest traditions, that of the Lansèt Kòd. Learn more about this iconic figure of the Haitian collective imagination.

The carnival has evolved over the decades to become a national holiday and Haiti’s most important cultural event. Today the atmosphere can be described as that of massive street parties, but it’s also an open-air showcase of artistic creations and craftsmanship.

Beyond the celebrations, the food, alcohol, and music, the Haitian Carnival also has a political aspect. The festival provides an opportunity for Haitians to express their popular grievances, through the costumes, the lyrics of the meringues and the songs that are played. The lyrics often contain demands and allegories of social life, which are delivered with the rhythm of the music and at full volume. And many costumes and carnival characters are made as satires and comments on current events.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

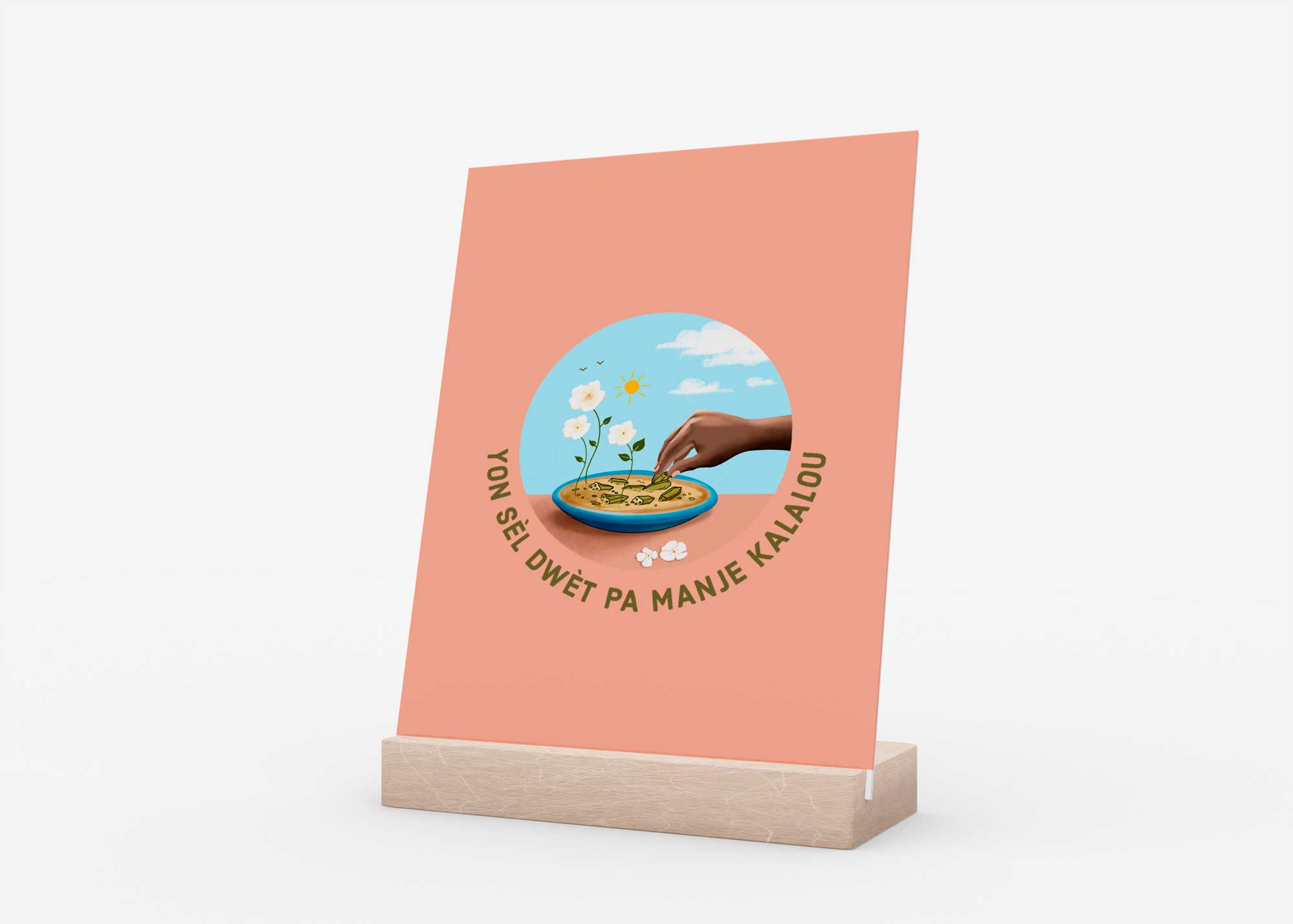

Colorful Costumes and Surprising Characters

If you ever find yourself at Carnival in Haiti (and believe us, you should) the first thing that’ll catch your eye is the stunning costumes worn by the carnival troupes. Made from papier-mâché, these outfits bring to life the country’s flora and fauna with bright colors and intricate designs. You’ll see everything from exotic birds like parrots and toucans to costumes inspired by the island’s colonial past.

But the costumes aren’t the only thing that makes the Haitian Carnival so special. The festival is also home to a wide range of colorful characters, both real and fictional. You might come across a larger-than-life portrayal of Barak Obama and Vladimir Putin or a whimsical depiction of Cholera or COVID-19. And don’t forget the historical figures, like the heroes of Haitian independence and the Taíno Indians, the island’s first inhabitants.

Each costume and character at the Haitian Carnival has a unique story to tell, representing different aspects of the country’s culture, history, and folklore. Looking to dive deeper into the fascinating world of the Haitian Carnival? Check out this visual guide, where we unpack the history and rich meanings behind the colorful costumes from Jacmel Carnival.

Photo: Franck Fontain

Carnival Music, Beats and Rhythms

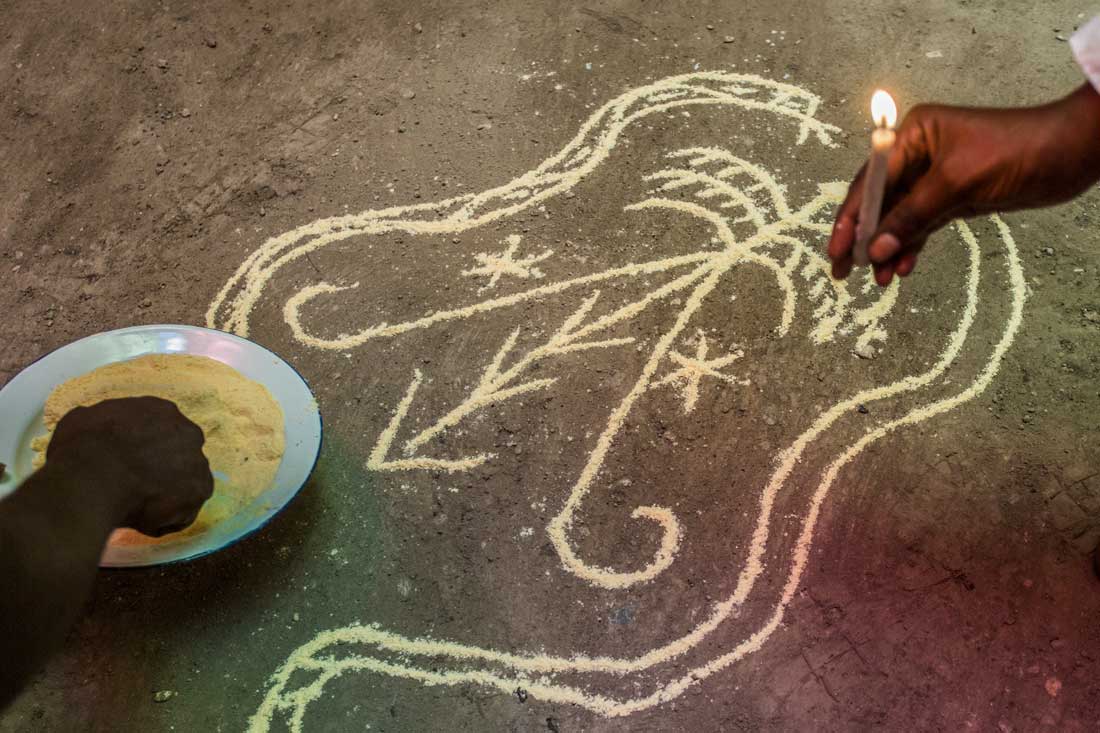

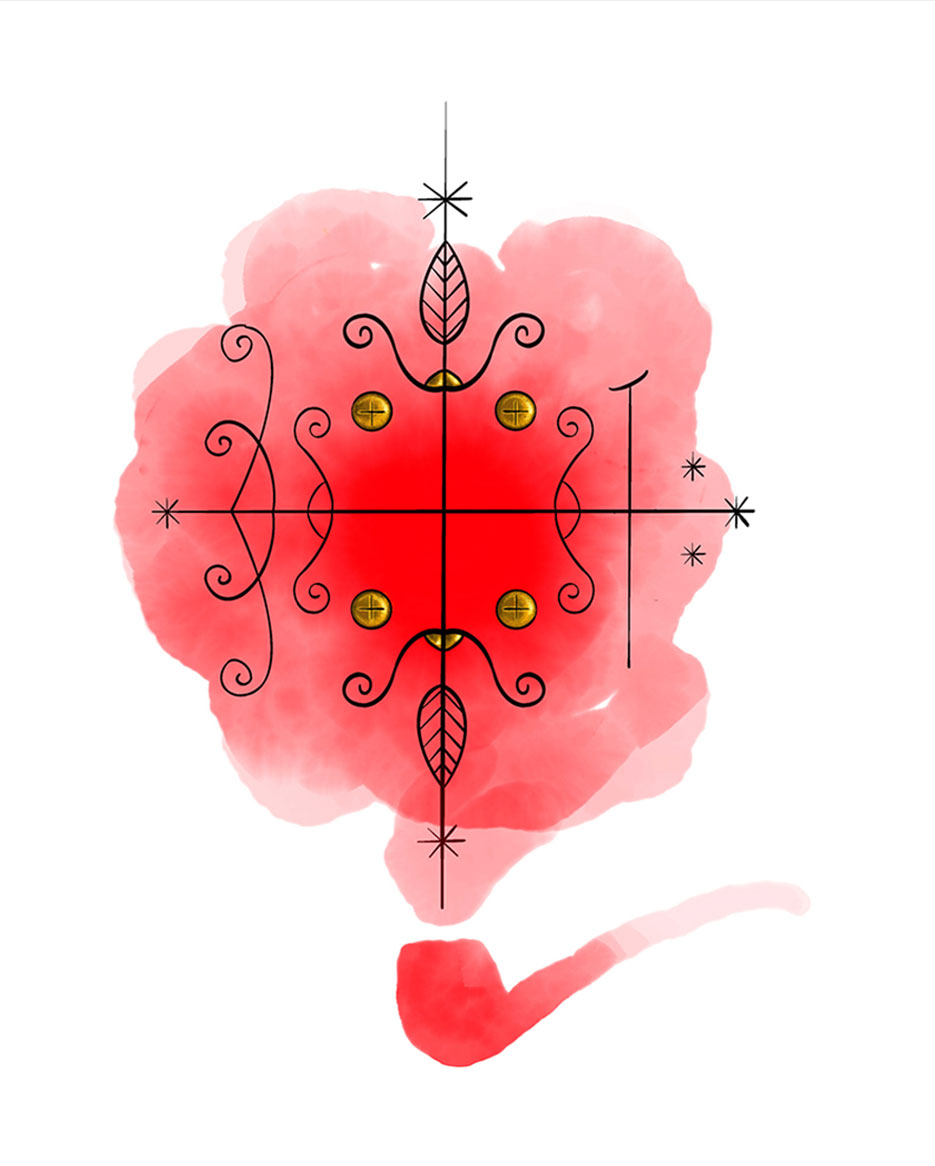

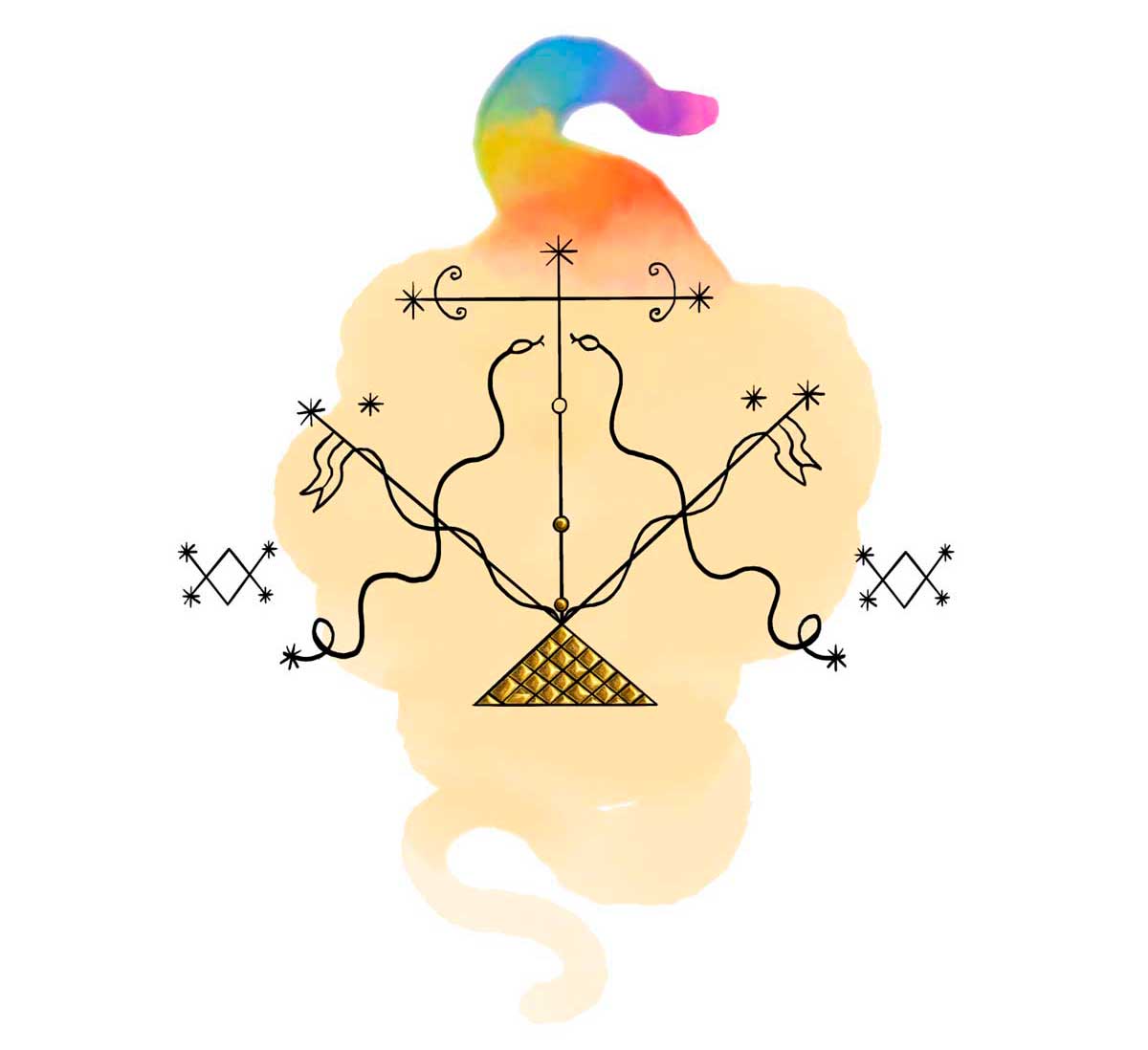

The music of the Haitian Carnival is a unique blend of European and African influences, creating a sound that is both lively and expressive, composed of percussion, bamboo instruments, trumpets, and accordions. At the heart of the carnival is the Rara, a traditional bann a pye (literally “bands on foot” or marching band) that is closely tied to the practice of Vodou.

In addition to Rara, the carnival is also influenced by other more modern music genres like the well-known compas, Creole rap, roots music, and raboday, which is a popular music genre that emerged in the mid-2000s. This genre is based on a traditional music style called “Rasin“, which mixes Vodou rhythms with modern pop-rock music. Raboday is often characterized by its energetic beats and heavy use of percussion, and it’s a favorite during carnival season and at dance parties all around Haiti. And last but not least, let’s not forget the meringue – one of the most popular styles of Haitian music you’ll hear during carnival.

Photo: Franck Fontain

Carnival flavors not to miss

Beignets

A staple of the Haitian kanaval tradition, beignets are a must-try delicacy during the carnival season in Haiti. Unlike traditional beignets, which are usually puffed fried batter, Haitian beignets are flat and made with bananas.

These delicious small treats have a similar appearance to mini crêpes but with a crunchy texture and are sprinkled with a generous amount of sugar. Don’t miss out on the chance to taste these sweet treats, as they are not commonly found outside of the carnival season.

Kleren

Another local flavor to try during carnival is “trampe” – a variety of the locally produced moonshine known as kleren (or clairin for French and English speakers). This type of artisanal rhum has a centuries-old tradition in Haiti and is an important part of the country’s culture. Trampe refers to kleren that has been macerated for weeks or even months with local fruits and spices, resulting in unique and flavorful blends.

During the carnival, you’ll find street vendors offering big jugs of kleren with various flavors and promises of health benefits and aphrodisiac properties. There are plenty of popular local trampe flavors to choose from, such as Kenep, which has a subtle sweetness from the Haitian fruit also known as quenepe or limoncello.

Bwa kochon is another popular flavor, infused with bark, wood, and leaves for an extra strong and earthy taste. Grenadya is a tangy and sweet flavor made with passion fruits, while Lanni is a sweet trampe infused with cinnamon, star anise, or fennel.

Photo: Franck Fontain

When is Carnival in Haiti

Carnival in Haiti is not a one-day event, as you might know it from other countries. In fact, it spans from January to the big parade during the Trois Jours Gras (three fat days) in February or March. Throughout the season, there are festivities and celebrations held every Sunday in many of the major cities in Haiti.

Whether you’re an art enthusiast, or maybe just want to party it up, there are several destinations you can choose from to experience it all.

Where to Experience the Haitian Kanaval

Jacmel

Jacmel’s carnival is a must-see for art lovers, with its out-of-this-world paper-mâché masks and glorious costumes crafted by local artisans and artists. The carnival of this sleepy coastal town is considered one of the most beautiful in the Caribbean due to the creativity and magnificence of its artistic displays. During the carnival season, Jacmel hosts several events and activities, leading up to the three-day celebration of Trois Jours Gras.

Want to party like a Haitian at Jacmel Carnival? Read this first!

Port-au-Prince

The Carnival in Port-au-Prince is the most popular in Haiti, attracting a large crowd of festivalgoers who come to enjoy the explosive atmosphere of music and dancing. The parade features artistic creations, marching bands, and large floats, but the real highlight is the musical groups that parade at Champ de Mars, the city’s largest public square. Here, the most famous Haitian bands and artists compete to see who will have the best carnival slogan, float, or song.

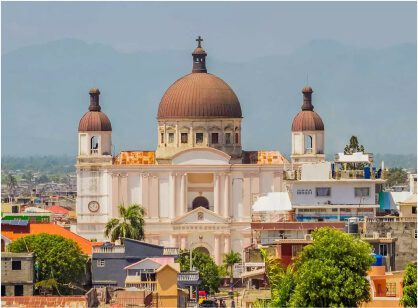

Cap-Haïtien

If you’re looking for a more peaceful carnival experience, Cap-Haïtien is a great choice. The parade takes place every year on the ocean-side Boulevard du Cap-Haïtien, which is also home to some of the city’s best restaurants. The Carnival in Cap-Haïtien is known for its orderliness and calm atmosphere, making it a great option for families and those who prefer a more relaxed celebration.

Written by Costaguinov Baptiste.

Published April 2023.

Explore Haiti’s Festivals & Events

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.