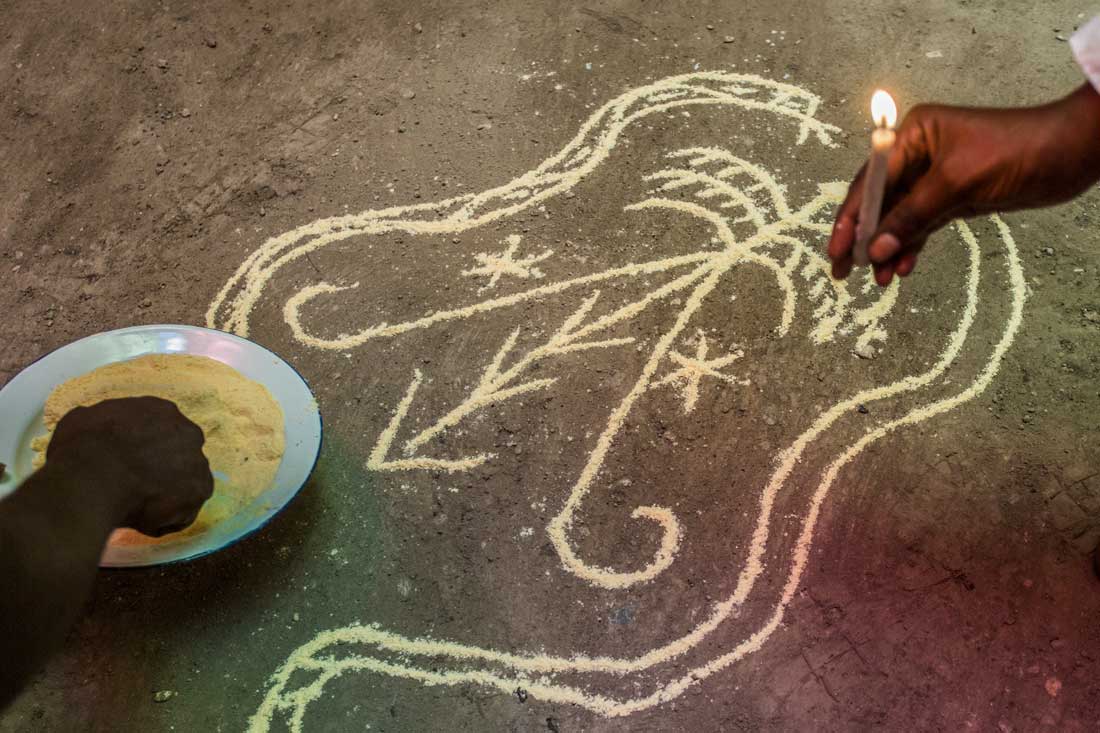

Photo: Mikkel Ulriksen

Great Haitian Charities to Support (and Those to Avoid!)

Whether you’re donating from a distance or only able to visit the project site briefly, it’s difficult to see what is (or isn’t) happening with your support. Here is a list of Haitian organizations you can support in good faith—and those you should avoid.

Don’t be misled

Recognisable charity names can be assuring, but sometimes the biggest and most established organisations are the ones with the worst track record of squandering donations to cover inflated administration costs and failing to effectively turn your dollars into genuine, on-ground change.

For over a decade, Haiti has been seen as a destination for altruism, with volunteers and donors hoping to support communities recovering from the devastating 2010 earthquake. Despite good intentions, hundreds of millions of dollars have been mismanaged, wasted, or funneled into ineffective projects that did little to help Haitians themselves.

The American Red Cross

After years of warnings from the Haitian community, a ProPublica and NPR investigation exposed how the American Red Cross misrepresented its work in Haiti. The organization raised nearly half a billion dollars for earthquake relief but built only six permanent homes—while pouring money into vague administrative costs. Well-meaning donors trusted ARC to deliver results, but instead, desperately needed funds never made it to local organizations that could have used them more effectively.

Oxfam

In one of the biggest humanitarian scandals in recent history, Oxfam aid workers were found to have exploited vulnerable Haitian women in the aftermath of the earthquake. Senior staff members hired sex workers—including minors—while on a relief mission, abusing their positions of power. When these reports surfaced, Oxfam initially tried to cover it up, and only later admitted to massive failures in oversight. The scandal led to a global reckoning on accountability in aid work, but for many in Haiti, the damage was already done.

The Orphanage Industry

Donating to orphanages might seem like a noble cause, but Haiti’s orphanage system is riddled with exploitation. Shockingly, 80% of children living in Haitian orphanages have at least one living parent. Many families are tricked into giving up their children, lured by false promises of education and care. Instead, many orphanages operate as money-making ventures, using children to attract foreign donations while neglecting their well-being. Reports have uncovered child trafficking, abuse, and severe neglect in many of these institutions.

Where Does the Money Go?

Even when charities aren’t engaged in outright abuse, the structure of foreign aid itself is deeply flawed. A look at USAID spending in Haiti found that only 7.6% of funds actually went to local organizations. The majority of aid money never reaches Haiti at all—it gets funneled through international contractors, overhead costs, and foreign NGOs, many of whom operate with little transparency or local input.

So Who Can You Trust?

Which charities are credible? Are there any on-the-ground volunteer projects where visitors can actually make a difference?

The key is to look beyond big names and flashy fundraising campaigns. Supporting Haitian-run organizations—the ones working directly with their communities, without bloated overhead or foreign decision-makers—ensures your money is actually making an impact.

Want to give to Haiti? Do your research, follow the lead of Haitians themselves, and make sure your support goes where it’s truly needed.

Photo: Franck Fontain

Haitian-Founded Organizations You Can Support With Confidence

Fortunately, there are many incredible Haitian-led initiatives working tirelessly to bring real, lasting change. These organizations are founded and run by Haitians who deeply understand the needs of their own communities—they have proven track records, transparent operations, and most importantly, a commitment to solutions that truly empower people on the ground.

Whether in education, healthcare, environmental sustainability, or economic development, these Haitian-founded and led organizations are doing the work that foreign aid often fails to accomplish. By supporting them, you’re not just donating—you’re investing in Haiti’s future on Haitian terms.

Fonkoze

Founded in 1994 Fonkoze is Haiti’s largest microfinance institution, dedicated to empowering rural communities—especially women—through financial services and education. By providing access to microloans, savings accounts, and financial literacy programs, Fonkoze helps entrepreneurs start and grow businesses, lifting families out of poverty.

Beyond microfinance, Fonkoze runs Chemen Lavi Miyò (Pathway to a Better Life)—a pioneering program designed to support Haiti’s most vulnerable women. Through a combination of cash stipends, food support, healthcare, and business training, participants gain the skills and resources to achieve financial independence.

With a strong commitment to women’s empowerment and community-driven solutions, Fonkoze continues to be a leader in breaking cycles of poverty and fostering long-term economic resilience in Haiti.

Support financial independence for Haitian women at fonkoze.org

The CHF Foundation

For over 32 years, The Centre Hospitalier de Fontaine Foundation (CHFF) has been a lifeline for communities in Cité-Soleil, one of Haiti’s most densely populated and underserved areas, often marked by extreme poverty and limited access to basic services. Founded by Jose Ulysse in 1991 and now led by Kareen Ulysse, CHFF operates with the guiding principle of serving where others don’t, when others can’t.

At the heart of its mission is the Centre Hospitalier de Fontaine (CHF), the only 24/7 medical facility in Cité-Soleil, providing life-saving care, maternal health services, and emergency treatment to thousands of residents. CHFF also runs Ecole Mixte Petit Coeur de Jesus, a school that offers education and daily meals to children, and CFPTF College, a vocational training program designed to equip young people with marketable skills and job opportunities.

Through its community-driven approach, CHFF is working to break cycles of poverty by ensuring access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunities for those who need them most.

Help CHFF bring healthcare and education to Cité-Soleil at chffoundation.com

P4H Global

P4H Global (Partners for Haiti) is a Haitian-led nonprofit organization dedicated to transforming education in Haiti through sustainable, locally driven teacher training programs. Rather than relying on short-term solutions, P4H Global focuses on equipping Haitian educators with the knowledge and skills needed to create lasting change in the country’s education system.

Founded with the belief that education is the key to breaking cycles of poverty, P4H Global works directly with schools and communities to empower teachers and improve learning outcomes across Haiti. Under the leadership of Dr. Bertrhude Albert, the organization has trained thousands of educators, reinforcing a model of self-sufficiency, excellence, and innovation in Haitian education.

Be part of the change in Haitian education at p4hglobal.org

FOKAL

Founded in 1995, Fondasyon Konesans Ak Libète (Foundation for Knowledge and Liberty)—better known as FOKAL—is a leading Haitian foundation committed to empowering local communities through education, economic development, and advocacy.

FOKAL supports smallholder farmers’ associations, grassroots women’s organizations, and ethical local enterprises—the true first responders in times of crisis and the strongest agents of grassroots resilience, self-care communities, local advocacy, and economic recovery. By investing in these Haitian-led initiatives, FOKAL fosters long-term, community-driven change rather than short-term aid dependency.

Support FOKAL’s mission by donating directly here.

Learn more at fokal.org

Grown in Haiti

In the mountains of Cap Rouge near Jacmel, Grown in Haiti is a sustainable, community-driven reforestation initiative founded in 2014 by Sidney-Max Etienne. In a country where deforestation and poverty are deeply interconnected, planting trees isn’t just about restoring the environment—it’s about empowering local communities with long-term resources and economic opportunities.

You can contribute by donating directly via the Grown in Haiti website. For those eager to take a hands-on approach, motivated volunteers are welcome to help maintain plant nurseries, share knowledge, and build community-driven skills that ensure lasting impact.

Get involved and donate at growninhaiti.com

Haiti Communitere

Located in Clercine, Port-au-Prince, Haiti Communitere is a dynamic community resource center that provides vital support to both local grassroots initiatives and international organizations. By offering resources, guidance, and sustainable working models, Haiti Communitere empowers small organizations to launch and expand their projects in a challenging environment.

Beyond its role as a support hub, Haiti Communitere has also led its own impactful initiatives across various fields, including language education, sexual health, and community development. Its primary mission is to foster locally driven solutions, ensuring that Haitian-led projects have the tools and space they need to thrive.

Get involved at haiticommunitere.org

Haiti Ocean Project

Based in Petite-Rivière-de-Nippes, Haiti Ocean Project is dedicated to the preservation and protection of marine life, including sea turtles, sharks, and rays. Operating in both Petite-Rivière and Grand Boucan, the organization not only works to safeguard Haiti’s rich marine biodiversity but also focuses on community education and sustainable fishing practices.

By raising awareness and promoting conservation efforts, Haiti Ocean Project empowers local fishers and young Haitians to become active stewards of their coastal environment, ensuring that Haiti’s marine ecosystems thrive for generations to come.

Learn more and donate here: haitioceanproject.com

Ayiti Community Trust

Ayiti Community Trust (ACT) is Haiti’s first and only community foundation, dedicated to fostering long-term, Haitian-led development rather than short-term aid. By focusing on civic education, environmental sustainability, and entrepreneurship, ACT supports local solutions that empower communities to create lasting change.

What makes ACT unique is its endowment model, which gathers resources from Haitians in Haiti, the diaspora, and global allies. Instead of relying on temporary relief efforts, ACT invests in grassroots organizations and local leaders, ensuring that change comes from within and is built to last.

Through its grant-making and advocacy, ACT is shifting the narrative around Haiti—moving away from dependency and toward self-sufficiency and long-term progress.

Be part of this movement for lasting change at ayiticommunitytrust.org

One of the Best Ways to Help Haiti? Visit and Support Local Businesses!

If you have the opportunity to visit Haiti, you’ll gain firsthand insight into the country’s realities and be in a stronger position to make informed decisions about how to contribute.

One of the most effective ways to support Haitian communities is through ethical tourism—spending your travel dollars directly with locally owned businesses. From staying at Haitian-run guesthouses to dining at family-owned restaurants and buying handmade crafts from local artisans, your presence can have a direct and positive impact on the economy.

Tourism provides a sustainable way to foster economic growth, empowering local communities where international aid has often fallen short. The cost of living allows for affordable travel while still enabling you to tip generously and support small businesses, ensuring your money stays within the community.

If you visit, make it count: stay, eat, explore, and celebrate Haiti with the people who call it home. And while you’re here, keep an eye out for Haitian-led organizations doing transformative work that deserves our collective support. Supporting local businesses and initiatives is one of the best ways to contribute to the development of this fiercely independent nation.

Written by Kelly Paulemon.

Published April 2020.

Updated February 2025.

Top things to see in Haiti

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.