Photo: Franck Fontain

Not Your Average Travel Guide to Jacmel (And That’s the Point)

One minute you’re in a jungle basin, the next in a papier-mâché workshop or Carnival chase. Jacmel is Haiti at its most alive.

This coastal city in the country’s southeast isn’t a checklist — it’s a feeling. Here, art drips from balconies, history clings to coral-stone walls, and wild nature beckons just beyond the city limits. We’re not here to tick boxes or sell you an itinerary — we’re here to wander, linger, and listen. Whether you’re sipping mountain-brewed coffee, running with black-painted Carnival troupes, or slipping into a turquoise pool deep in the jungle, Jacmel doesn’t just welcome you — it pulls you in. These are the stories, the steps, and the soul-stirring detours that make this one of Haiti’s most unforgettable escapes.

Photo: Franck Fontain

1. Walk the Coffee Route in Fonds Jean-Noël

High in the misty mountains above Marigot, this guided walk offers a slow, grounding escape into Haiti’s agricultural soul. Led by a local farmers’ co-op, the trail winds through groves of shade-grown coffee, fruit trees, and medicinal plants. Along the way, you’ll learn how beans go from seedling to cup, roasted over open flames and brewed the old-fashioned way — just like Haitian grandmothers still do.

Expect coconut breaks, impromptu dancing, and a final cup of the smoothest brew you’ve ever had. Reaching the village takes around 90 minutes from Jacmel — best tackled with a guide and a 4×4.

Photo: Franck Fontain

2. Wake Early for Market Day in Marigot

If you’re heading to Fonds Jean-Noël, aim for a Saturday — it’s the perfect excuse to stop in Marigot on the way. Just after dawn, this quiet coastal town transforms into a bustling harbor market. Massive wooden boats sail in from Haiti’s far southeast, their hulls hand-painted with gospel verses and bright colors, much like the country’s iconic tap-tap buses. They unload glistening fish, sacks of produce, and cassava by the armful.

What starts as a calm hum builds into a full sensory overload: shouting vendors, rumbling trucks, sizzling fritay, and the occasional burst of diesel smoke. It’s raw, unfiltered, and completely local — few visitors make it this far east. Come early, bring small bills, and go slow. And if you’re carrying a camera, remember: in Haiti, permission is everything. Ask before you shoot, and maybe buy a handful of oranges while you’re at it.

If the market’s rhythm caught your attention, don’t miss our full Photo Journal on Marigot.

Photo: Franck Fontain

3. Chase Waterfalls in Jacmel’s Jungle

Ask anyone in Jacmel where to go, and they’ll point you toward Bassin Bleu — a sequence of surreal, electric-blue pools tucked deep in the jungle. It’s Haiti’s most iconic waterfall, but don’t mistake it for easy access.

The four basins — Cheval, Yes, Palmiste, and Clair — unfold like secrets, each more striking than the last. To reach the final pool, Bassin Clair, you’ll climb slippery ledges and lower yourself down a rock face by rope — but the payoff is 75 feet of luminous turquoise, where locals float and dive in suspended calm. Come early for the best light and fewest crowds, and avoid visiting after rain, when the water can turn cloudy and currents unpredictable. Bring water shoes, small bills for a guide, and let the jungle silence replace the outside world.

Ready to chase the falls yourself? Start with our in-depth Bassin Bleu guide.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

4. Go Surfing in Kabik

Far from the tourist trail, Kabik Beach is a hidden swell magnet near Cayes-Jacmel, where the waves are consistent, the water is warm, and the lineup is often empty. Mornings are glassy — perfect for beginners launching from nearby Ti Mouillage. By afternoon, trade winds roll in and the bigger breaks come alive, drawing local pros and the occasional traveler. Waves can hit 10 feet during peak season (February to November), and while surf schools are rare, local instructors can be found — just ask around.

Stay overnight at Haiti Surf Guesthouse, a rustic eco-lodge tucked in the hills above the beach. Wooden bungalows sit beneath towering trees, and a creek-fed pool slices through the jungle like a secret. The vibe is slow and unplugged: strong coffee in the morning, strong rum at night, and all the time in the world between.

Want to know where to catch the best waves in Haiti? Our surfer’s guide has all the details you need.

Photo: Anton Lau

5. Take a Walking Tour Through Jacmel’s Historic Core

Jacmel isn’t just seen — it’s felt. The best way to absorb the city’s layered soul is by walking through its historic center, where 19th-century merchant houses line the streets with lacy ironwork, coral-stone walls, and fading grandeur. Start at the old iron market, shipped from Belgium in 1895, then follow Rue du Commerce past the customs house, once the heart of Haiti’s coffee trade.

You’ll pass wooden balconies, shuttered windows, and quiet courtyards that still echo with stories of merchants, poets, and revolutionaries. The cathedral stands watch over it all, its baroque silhouette nodding to faraway influences from Cuba and Spain. Local guides can bring it all to life, but even on your own, the textures of the city speak volumes. Wear good shoes, go slow, and let Jacmel reveal itself — one façade, one footstep, one memory at a time.

Photo: Franck Fontain

6. Day Trip to Cascade Pichon in Belle-Anse

Hidden between thick forest and remote hills, Cascade Pichon is one of Haiti’s most spectacular waterfalls — and also one of its best-kept secrets. Fed by an underground lake, its waters tumble into three turquoise basins: Chouket, scented with wild mint; Dieula, deeper and shaded; and Marassa, where light skips across the surface.

Getting here is part of the magic. From Jacmel, the trip can take up to four hours by 4×4, moto taxi, and a 40-minute hike on foot. The route winds past beaches, mountains, and far-flung villages few travelers ever see. At the end, a cool, hidden swim awaits — quiet, wild, and unforgettable. Bring a guide, pack light, and breathe deep.

Planning the trek already? Read our full guide to reaching Cascade Pichon.

Photo: Jean Oscar Augustin

7. Go Wild with a Lansèt Kòd Group During Carnival Season

Every Sunday from January to Carnival, Jacmel’s sleepy streets erupt in stomps, whip cracks, and rebellious drumbeats — your cue that the Lansèt Kòd are on the move. In this century-old ritual of satire and survival, local men and boys cover themselves in sticky black paint, don ragged costumes, and charge through town in joyful, chaotic packs.

Ask your host or guide to connect you with a group. You’ll learn to mix the paint (charcoal and cane syrup), dress the part (horns, wigs, old clothes), and keep pace with the rhythm. Eccentricity is the point. Swigs of kleren — Haiti’s fiery moonshine — fuel the frenzy as black handprints fly. By sundown, everyone plunges into the sea for a cleansing, full-body exhale.

Eager to understand this unique Haitian tradition? Explore the full story of the Lansèt Kòd in our article.

Photo: Anton Lau

8. Hike Up to Fort Ogé

Perched on a mountaintop east of Jacmel, Fort Ogé is a 200-year-old stone outpost built in 1804 and named after revolutionary Vincent Ogé. It’s smaller than the Citadelle up north — but that’s part of the magic: no crowds, no gates, just quiet ruins, sweeping views, and the occasional soccer game inside the old walls.

Ask a moto driver to take you up (it’s a rough ride), and bring a few gourdes for local guides who’ll walk you through dungeons, cannons, and stories etched in stone. The whole visit takes under an hour — but the breeze, the view, and the weight of history linger long after.

The view’s just the beginning — read our in-depth guide to Fort Ogé.

Photo: Grown in Haiti

9. Explore Haiti’s Coolest Permaculture Project

Up in the mountains of Cap Rouge, not far from the road to Fort Ogé, Grown in Haiti is a lush, off-grid reforestation site where rare tropical trees, fruit forests, and permaculture principles thrive. It’s not open to drop-ins — you’ll need to message them on Instagram to arrange a visit — but once you’re in, expect a quiet, eye-opening tour through acres of regenerative agriculture.

The project focuses on tree-planting, seed-saving, and sustainable living, led by a team that’s deeply rooted in the land. You’ll walk among jackfruit and cacao, explore a hidden spring, and learn how native species are brought back to life. It’s not a full-day excursion, but it’s the kind of place that stays with you — calm, wild, and quietly radical.

Want to support more places like this? Check out our guide to Haitian organizations worth backing.

Photo: Franck Fontain

10. Step Inside Jacmel’s Creative Heart

From towering papier-mâché masks to vivid paintings and handmade crafts, Jacmel’s streets pulse with artistry — and nowhere more than in the ateliers of Lakou New York and the Jacmel Arts Center. This walkable hub in the historic center is home to some of Haiti’s most prolific Carnival artists. Reach out in advance — you might catch a master like Charlotte Charles at work, or even join a hands-on workshop.

Just around the corner, the Jacmel Arts Center — housed in a restored 19th-century building on Rue Ste-Anne — blends gallery, school, boutique, and performance space under one roof. Led by a collective of 100+ artists, it’s as much about community as it is about creativity. Come for the tour, stay for the conversation — and let the color seep in.

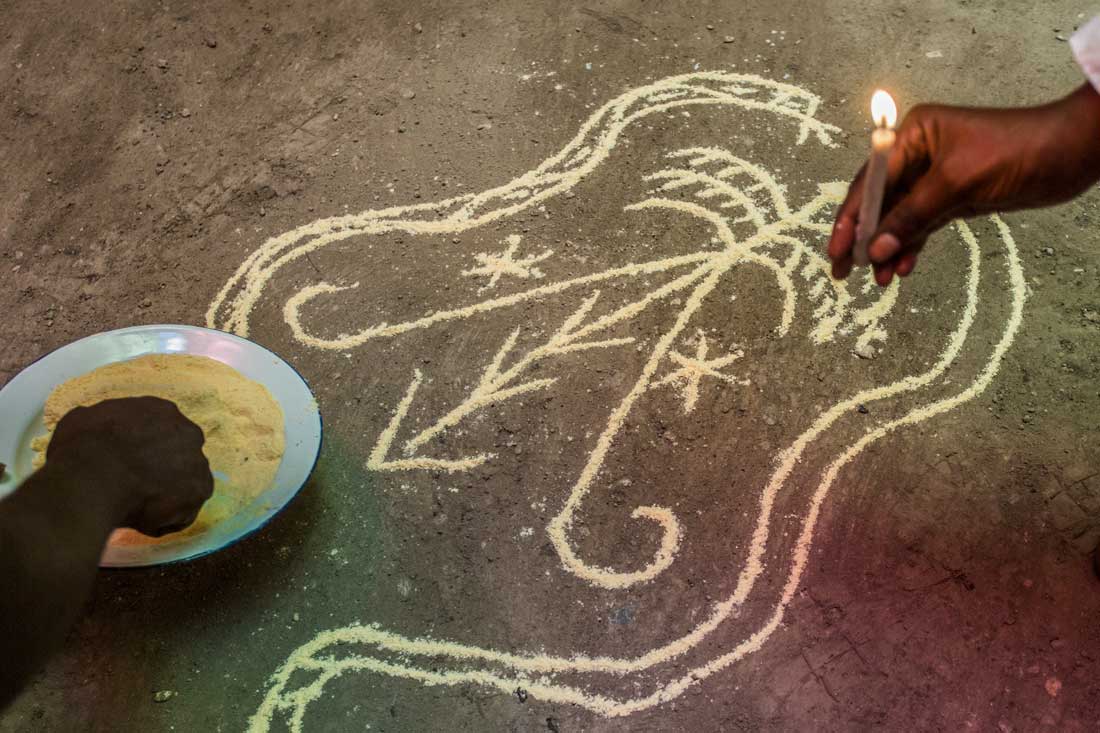

Photo: Pierre Michel Jean

11. Attend a Vodou Ceremony

More than skulls, sequins, and smoke, a Vodou ceremony is a sensory plunge into Haiti’s spiritual soul — rhythmic, raw, and deeply alive. If you’re lucky enough to attend one around Jacmel, expect pounding drums, flickering candles, and dancers who give their bodies to the spirits in a trance-like communion called possession.

You’ll need a local guide to connect you — these aren’t staged performances but real rites of healing and connection, often held at a peristil temple or under a sacred tree. Dress respectfully (but not in white), bring a bottle of kleren as an offering, and arrive with an open mind. Forget mainstream Hollywood portrayals — what you’ll find is reverence, rhythm, and a celebration of life that’s rooted in centuries of resistance and resilience.

Intrigued by Haiti’s spiritual roots? Our Vodou ceremony guide goes deeper.

Top things to see in Haiti

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.