Photo: Anton Lau

Unreal art at Galerie Monnin

Galerie Monnin is a space that beautifully balances the old and new, the imaginary and the real. This 50-year old gallery is one of the top attractions in Haiti and brings you the best of Haitian art, old world antiques and a new take on creative events in a mysterious setting.

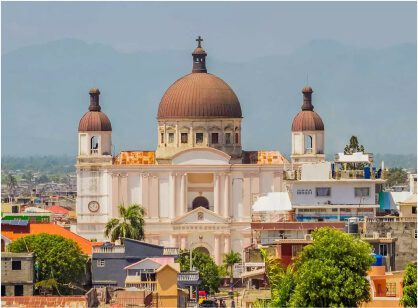

Leave behind the cobblestone pavement in the mountains of Laboule, above Port-au-Prince, and pass through a stone archway set into a bright two-story villa covered in comic book style illustrations.

Inside the gates is a kind of whitewash-and-ebony mansion that seems more at home in a Swiss fairy tale than the cobblestone Haitian streets. The next thing you notice is the silence. The hustle and bustle of the capital exists outside of this tropical forest enclave. An oversized broken clock and mosaic-tiled skull in the entrance hint at the wonder that awaits inside.

Photo: Anton Lau

Enter the weird

The first room is styled like an 19th century living room. You’re greeted by floor to ceiling gallery walls with all manner of Haitian art, vintage furniture and modern lighting. Through the narrow doors, you’ll follow a myriad of narrow passageways into adjoining rooms, each a unique combination of antiques and neon-modern art.

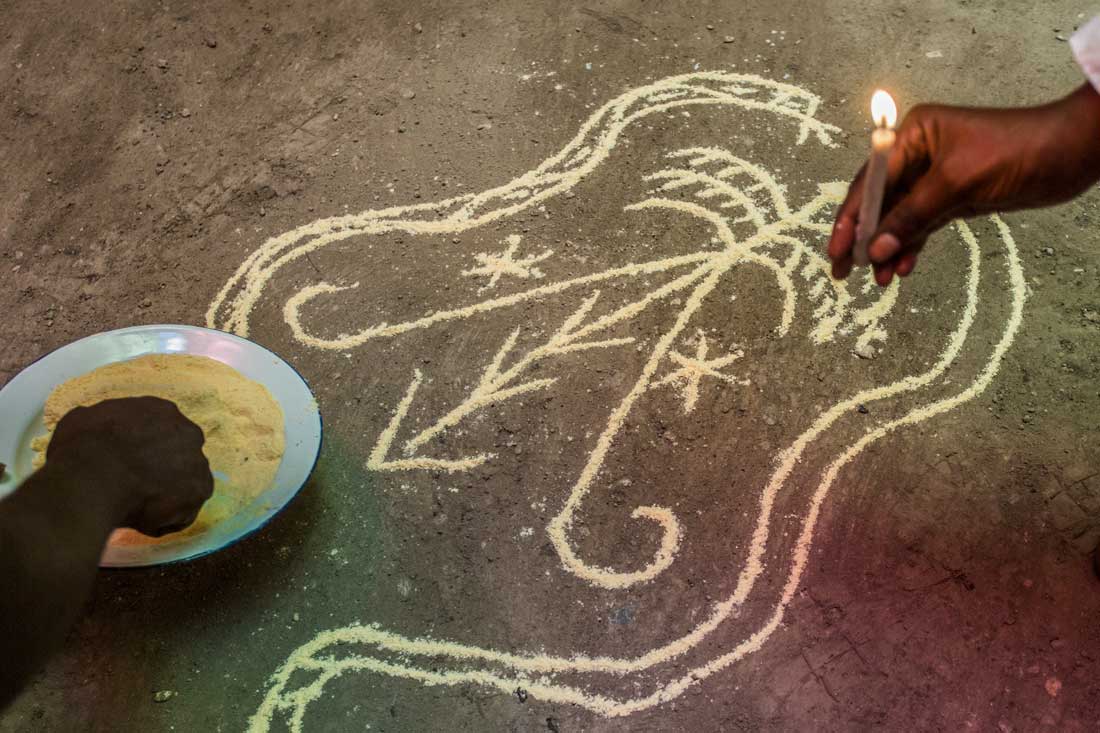

Room after room, hidden balcony after hidden terrace you are drawn inward toward more of the unexpected. It’s perfectly curated bohemian-Vodou-madness with plenty of high-calibre art and an undercurrent of mystery. And it’s all for sale.

For a touch of gothic or what may be considered creepy to non-initiates, visit the room dedicated to assemblage Vodou sculptures and doll heads. The creepy figurations and inscrutable symbolism of traditional Vodou art are jumbled up with their garish neon counterparts. In the final room, a vintage settee and antique Vodou flags sit next to a freshly painted selfie booth. It’s complete with modern mirrors, and invites you to take a snap for yourself.

Photo: Anton Lau

A family affair

This Caribbean homage to all things weird and thought-provoking is owned by two sisters. Curator and art director Gaël Monnin and world-famous artist Pascale Monnin joined forces to transform their family’s property into a new kind of exhibition space unparalleled in the Caribbean.

Gaël and Pascale are the third generation in a long history of Monnins in Haiti. Originally Swiss art promoters, the Monnins first settled here back in 1944. It was at the time when the New Yorker Dewit Peters launched the Centre D’art in Port-au-Prince and turned the naïve Haitian painting style a world-wide collectors trend.

The first generation of Monnins befriended Peters and bought paintings from artists who would became famous as the great masters of the naïve Haitian painting style (Hector Hyppolite, Castere Bazile, Rigaud Benoit, Préfète Duffaut and many others) and participated in creative lifestyles themselves.

Galerie Monnin was first launched in 1956, and for the last 50 years it has since fostered art, forged friendships, curated exhibitions and contributed to the cultural development of Haiti.

Now in its third generation (and third location), Galerie Monnin’s history is the story of a family woven deeply into the creative fabric of Haiti. As patrons of the art, the Monnins, like the artworks on their walls, bear witness to the angels and demons that have plagued the political landscape over the decades.

In recent years, sisters Pascale and Gaël Monnin realized that a facelift to rejuvenate the gallery was necessary, and in 2018 they moved the massive collection up to Laboule 17 and curated the complementary décor throughout.

Photo: Anton Lau

About the collection

The gallery’s permanent collection ranges from the leaders in naïf art, the masters of Saint Soleil (Sen Soley) painters and a broad collection of internationally-significant Haitian artists. It’s also the place to find the latest works from contemporary masters.

You’ll find works from KILLY, PASKO, Mario Benjamin, NASSON, and David Boyer. Naturally, the works of Pascale Monnin, internationally renowned in her own right, are regularly exhibited here. She can be found on the gallery grounds, creating new pieces with her collaborators.

Photo: Anton Lau

More than art

Beyond the classic work of curating and representing Haitian artists, Galerie Monnin has become an integral platform for the broader creative community. Innovative events and activities happen weekly in the leafy gardens of Laboule 17.

Since reopening at the new location in early 2018, Galerie Monnin has hosted fashion collection launches, artist workshops, book signings and weekly networking events for creatives.

Looking for a chance to breathe deeply, surrounded by tropical forest? Galerie Monnin offers yoga once a week. All week long, stopping at the galllery is a brilliant way to take a time out on the way up or down the Kenscoff road.

Getting there

Not familiar with Port-au-Prince? This exceptional space is tucked away in an enclave on Kenscoff road but easy to find if you know where to look. Don’t be fooled by Google Maps, which may still point you to the old address. Instead, head south out of Pétion-Ville on Route de Kenscoff and drive west until you reach a road marked Laboule 17. The roads are clearly marked, but note that each road has its own number – so the road marked Laboule 18 is a different road entirely.

Turn left at the sign styled like a Medieval shield, with “Galerie Monnin” printed on it. You enter a private driveway and continue driving through the lush parkway, past a security guard, until you arrive in front of a series of stone houses. The private residences lie to the left. Front and center lies this hidden gem of a gallery, waiting to be discovered.

Written by Emily Bauman.

Published October 2018

Find Galerie Monnin

External Links

Learn more about the Gallery

Check out Galerie Monnin’s Facebook page

Explore Haitian art and culture

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.