Photo: Mikkel Ulriksen

Explore the enchanting ruins of Fort Saint-Louis

A microcosm of Haitian history

The overgrown ruins of this 300 year-old French-built fort will enchant visitors for hours (and archaeologists for days), but to get there you’ll need to hire a boat.

Fort Saint-Louis stands on an islet in the Bay of St Louis, and is accessible via a short boat ride from Fort de Olivier, a fortress on the nearby peninsula of Saint Louis du Sud. Constructed at the same time, these two forts are often called ‘sisters,’ and are two of many strategically dotted along the coastline.

Just outside the seaside fortress, an abandoned shipwreck peeks up from underwater. For locals, this shipwreck is a microcosm of Haitian history. Across the country, relics of more dangerous times dot the landscape, their defences now serving to preserve cultural memories instead of material treasure, and changing over time as the years and the tropical storms assert their strength.

Photo: Mikkel Ulriksen

The extensive ruins of modern-day Fort Saint-Louis rise steeply from a craggy islet, the curtain wall of stone now thickly overgrown with vines and trees that blow in the tropic coastal breeze. After three hundred years of equatorial sunshine, sea salt and hurricanes, the outline of the fort is in remarkably good condition, and it’s still possible to walk through its many chambers and admire the original carved features set into the outer walls. You can still walk through some of the caves originally networked into the fortress.

Walking under the arches of the structure of the fort with branches and lianas hanging left and right feels surreal; it is almost as though you are one of the shift guards, waiting for the British to invade at any moment. Although severely weathered, the fort feels as towering and as imposing as it must have been three centuries ago.

Fort Saint-Louis

Photo: Mikkel Ulriksen

Built in 1702 by French occupiers, Fort Saint-Louis was designed to defend the Haitian territory against their colonial competitors – namely the British Empire. In 1748, less than fifty years later, the was captured by the British. As a result, it’s now known as Fort des Anglais by many locals.

The southern coastline of Haiti was hotly contested in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a foothold from which to defend the country’s riches. Although modern Haiti is known for its pristine beaches, colonial-era Haiti made a name for itself in European cities through the high-quality goods brought back by traders returning from its shores. Fort Saint-Louis was built just five years after the French and Spanish divided up the island of Hispaniola into two separate countries – Dominican Republic on the East and Haiti on the West.

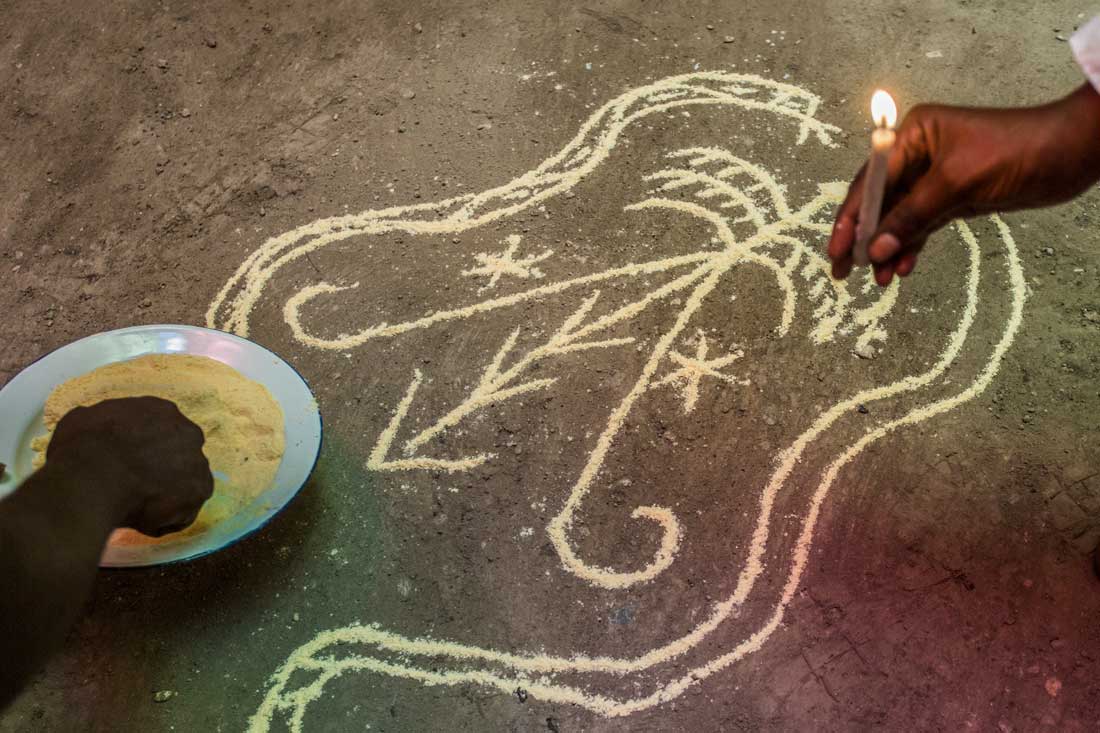

Photo: Franck Fontain

Getting there

Fort des Oliviers is located on a small peninsula in Saint Louis du Sud. From there, Fort Saint-Louis is on a small island a short boat ride away. For a small fee, the local sailors offer their boats – and often times, dugout canoes – as a mode of transportation.

Get the most out of your visit

Tour guides, who often live nearby in Saint Louis du Sud, or in the areas surrounding Fort des Oliviers, are always ready to provide their services by accompanying visitors and talking them through the history of the fort and the features that have stood the test of time.

Today, Fort Saint-Louis stands as a testament to a period in time and a state of mind that permeate the way modern Haitians understand and process their history.

Walking through the fort with someone who lives the complexity of that history is the best way to gain a nuanced understanding of what this beautiful ruin means.

Written by Kelly Paulemon.

Published March 2019

Find Fort Saint-Louis

External Links

Read more about Fort Saint-Louis

Recommended

Paradise for your inbox

Your monthly ticket to Haiti awaits! Get first-hand travel tips, the latest news, and inspiring stories delivered straight to your inbox—no spam, just paradise.